21st century, second decade

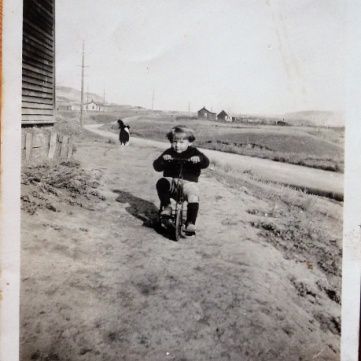

My parents died at the beginning of the second decade of the new century, a year apart to the day. Several close friends died. My sons married their sweethearts. (My daughter married hers a few weeks ago!) Every day held sorrow and joy. And also a sense of possibilities for my long-held interest in my family’s history. After my father’s death, I took home the small hoard of papers and photographs he’d kept to himself. I don’t know exactly why he was reluctant to share the materials, or to pursue answers to questions–the ones I had and surely ones he had too? And a year later, after my mother’s death, I felt the uneasy sense that I was now the family matriarch, the one responsible for keeping the lines of kinship clear. They were not clear. There were half-stories, careless genealogies. In retrospect, I see that much of the research and writing I did during this decade was in service to these histories.

I’ve always loved the literary novella. Without ever really intending to, I’ve built up a nice collection and have read many more, via library or generous friends. Inishbream was a sort of accidental novella, beginning as it did as a linked group of prose poems, eventually drawn out and given a structure. I loved the possibilities of the form, how it could hold so much in such a hermetic shape. A year or two after The Age of Water Lilies was published, I was invited to a book club to talk with members who’d just read it. I always enjoy these occasions. During our time together, one woman asked what happened to Grace after the novel ended. Good question. Grace was born to a single mother in the spring of 1915. She is sort of tangential to the narrative. But the more I thought about her, the more I wondered too. I began to write Winter Wren to find out. I think I knew from the beginning that the book would be a novella. I put Grace in a cabin I’d always thought I’d like to live in, a cabin I first saw as a teenager, on a beach west of Sooke, B.C. (It’s the one above the waterfall in the photograph at the beginning of this post.) She was in her late 50s, an artist trying to paint the view at dusk. I wanted to write about the 1970s—the novella takes place in 1974, an interesting time for ceramics in B.C. (Grace’s love interest is a potter in the tradition of those who studied with Bernard Leach in Cornwall and then returned to Canada), for museums where the salvage paradigm was part of the ethos, and perhaps the last possible time for Grace to meet one of the late 19th c-early 20th c artifact collectors.

But you know already what I’m going to say: I sent Winter Wren to dozens of publishers and all of them rejected it. To make a long story short, my dear friend Anik See was visiting enroute from Dawson City to the Netherlands and we shared similar stories about novellas we’d written. We decided to begin a micropress to showcase the form and we decided to begin with mine. Our rationale was this: if our endeavour didn’t work, then I would be disappointed, sure, but at least it would only be me and not someone else. I could shake it off, poof, and move on. (Ha!) Anik designed the book, I photographed a pottery dish with a length of scouring rush (it figures in the book), and we found a really good printer in Victoria. And you know, we sold our first print run of 250 copies within weeks and we reprinted. I still get orders for it. We went on to publish 4 more novellas and we are very proud of Fish Gotta Swim Editions. Our latest is Anik’s Cabin Fever.

I’ve been to the small Vancouver Island beach near Jordan River where Theresa Kishkan’s novella Winter Wren (Fish Gotta Swim Editions) is set; I’ve seen the waterfall that tumbles over sandstone onto the shingle just below, and the solitary cabin facing south and west, surrounded by salal. Winter Wren tells one possible story from the many that cabin could tell. (Michael Hayward, Geist)

After I finished writing Winter Wren, I wrote another novella, Patrin, and it was published (beautifully) by Mona Fertig’s Mother Tongue Publishing in 2015 and then in French by Marchand de Feuilles in 2018. I also wrote a long essay, “Euclid’s Orchard”, about quilting, mathematics, coyote music, apple trees, and love; and when Mona showed interest in publishing a collection of my essays, I gathered together a group. Eulid’s Orchard & Other Essays was published in 2017 and was shortlisted for the Hubert Evans Award.

Each image is a perfect crystallization of a detail, gesturing toward a truth much larger than the tiny pinpoint of its composition. Near Victoria, she recounts an exquisite memory of “an abandoned house completely knitted into place by honeysuckle and roses” (p. 101). Near Drumheller, she sings the prairie: “turn, turn, bend the song to the roadside plants … free verse composed of craneflies, dragonflies, bluebottles, broad-bodies leaf beetles, greasewood and cocklebur” (p. 61). And near her home, she concludes with the cries of coyotes: “lilting joyous youngsters unaware that a life is anything other than the moment in the moonlight, fresh meat in their stomachs, the old trees with a few apples and pears too small and green for any living things to be interested in this early in the season” (p. 155). (Catriona Sandilands, The British Columbia Review)

An aside: Mona Fertig and her Mother Tongue Publishing enterprise deserve gratitude from writers everywhere for the beauty of the books and the huge effort Mona put into designing them, editing them, bringing them into the world with sparkling wine and flowers, arranging public events for the writers, and being the kind of publisher writers dream of. I’d have published with her forever and was sad when she announced her retirement but also glad for her because she’s been able to return to her own writing projects. She did everything that bigger publishers did and she did it with joy. (She’s the one on the left, with the big smile.)

Novellas, novellas. I wrote The Weight of the Heart as a way to lament the gaps in my own education in the 1970s when the instructor of my Canadian literature course told me not to bother writing about Sheila Watson and Ethel Wilson, saying they were minor, and the former was barely coherent. I wanted to celebrate these two literary cartographers of our province and to highlight the importance of their work. I also wanted to spend time, real time and imaginatively, in the Thompson Canyon and the dry Interior of B.C. Palimpsest Press published The Weight of the Heart in the spring of 2020, just as most publishers and some writers were required to pivot to a virtual presence because of the pandemic. I wish I’d been better at this, though we still had such a slow internet connection—we live in a rural area– that even if I had been able to Zoom more effectively, our bandwidth wouldn’t have allowed me to participate much. (We were able to upgrade a bit later.)

The Weight of the Heart also finds in Wilson’s and Watson’s writing an experimental style and a mode of consolation. Like Wilson’s independent protagonists, the narrator discovers her autonomy and grit in the landscape she travels. Watson’s spectral figures and interest in sacred rituals resound in the symbolic scenes of almost drowning in which the narrator is saved by her brother’s mysterious presence and in Kishkan’s invocation of Egyptian burial rites as a refrain throughout. Most obviously, the double hook of Watson’s title recurs in the dualities throughout the novel—in the two rivers, in twin foals (the colt unfortunately lost in birth) by a mare named Angel, and most clearly in the two siblings who are bound together in a landscape where life and death regularly meet. So, Kishkan and her narrator know where to look in Canadian fiction for a view of the British Columbian landscape that reveals these striking oppositions and their consoling unions. A unique and compelling creation in its own right, Kishkan’s poetic exploration of grief lives up to its literary precursors. (Kait Pinder, the Malahat Review)

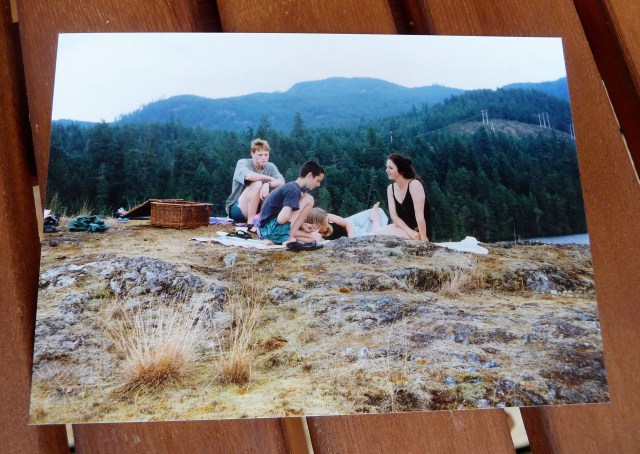

I wrote another novella in this decade, begun perhaps in the middle, put aside, but finished in 2020, during the long lonely weeks of the pandemic when I was missing my family and wondering if we would ever get together again for our summer meals, swims, and talks late into the night by a campfire. I used Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway as a template, following the main character through a day of preparations for a party. There are shadows and owl voices in the woods and an unexpected guest coming up the driveway at dusk, carrying a knife. I tried to find ways to present the material innovatively, with sections of call and response, lists, and the music of an oud. I called it The Occasions. I don’t know if it will ever be published.

Another aside: I am lucky in life and love if not in publishing. And I wonder how many writers have a husband who is also a letterpress printer and who offers to make keepsakes to celebrate new books? For the past ten years or so, John has printed beautiful objects, some of them embellished by me, to give away at book launches and to provide local book stores with so they can tuck a keepsake into the books of mine that they sell. I have a few remaining of some of these and if you want to order a book from me, I can include one for you.

At the beginning of this instalment, I wrote that I was trying to untangle the knots of family history and genealogy. Some of this work resulted in essays in Euclid’s Orchard but I wasn’t finished and kept on writing. I’d also had a health issue in 2016 that resulted in many tests, half-diagnoses, fearful assessments (though it all worked out well), and I also wrote about those things against the backdrop of all I loved: my family, the rivers of this province, textile work (which is always a way of meditating for me, sewing myself in and out of mysteries, riddles), the countries my grandparents left for new lives in Canada, and more. These became Blue Portugal & Other Essays, published with care and generosity by the University of Alberta Press in 2022. It received SUCH good reviews.

In Blue Portugal the essays’ themes are allowed to slip their boundaries; a topic addressed in one essay recurs in later essays, a recognition, perhaps, that thoughts and interests develop over time, shifting slightly as they are put in the company of other thoughts, are seen from different perspectives. The essays in Blue Portugal seem to talk to each other; they interlace in interesting and thought-provoking ways. The book is a fine example of the personal essay at its best. (Michael Hayward, The British Columbia Review)

It was a book that others noticed, gifted to friends, and reading it now, I am sort of surprised that I was led into some of the essays so mysteriously. A voice in the night, murmuring, The river door. Whose voice? I only know I took it to heart.

To those of us who’ve been following Theresa Kishkan on her blog for many years, the preoccupations of her latest book, the collection Blue Portugal & Other Essays, will be familiar, the quilts, the homesteads, the memories, the blue. But it’s the stunning craftsmanship of the book, the fascinating threads that weave the pieces together and also recur throughout the text, that make this book such a pleasure to discover. How quilting squares are analogous to the rectangles from which, one by one, Kishkan and her husband literally constructed their home on BC’s Sechelt Peninsula, and the blueprints, and the blues of dye, and of veins, and of rivers, and of how one thing turns into another—how? How does a body get old? How do children grow? How does a family tree sprout so many new branches? And from where did it all begin, Kishkan going back to seek her parents’ nebulous roots in the Czech Republic and Ukraine, in a 1917 map of lots in Drumheller, AB, in everything that was lost in the Spanish Flu, and how we’re connected to everything our ancestors lived through. (Kerry Clare, picklemethis.com)

And now? Now? 4 years into the 3rd decade of the century, I’ve completed another collection of essays. The centrepiece is a long postmortem and reassessment of a relationship I had with a painter when I was 23 years old. My walls are hung with some of his paintings, portraits of me among them, and I attempt to reclaim the gaze by entering into a daily conversation with one particular portrait hung in a stairwell; she is one of the first things I see each morning as I come down to the kitchen. There are other essays in the collection that meditate on war, climate change, injury and recovery, swimming and Herakleitos, and the nature of love. I’ve begun the long process of trying to find a publisher (my last publisher wasn’t interested, feeling perhaps that the collection is too personal and potentially risky in terms of sexual politics). As I write, it’s been rejected by 4 publishers and is currently awaiting decisions by 6 more. I’m also about halfway through writing a novel set in a small fishing village called Easthope and in the city of Lviv, in western Ukraine. I began the novel 4 years ago, just home from a trip to Ukraine, and set it aside to complete editorial work on Blue Portugal. And then the Russians invaded Ukraine and I couldn’t imagine ever writing about Lviv. But I decided that I’d stay with my original intention and setting— 2015—and write to set down what I love about both places.

And now in a hurry just

pack, always, each day,

and go breathless, go to Lvov,

after all it exists, quiet and pure as

as a peach. It is everywhere.–Adam Zagajewski, trans. Renata Gorezynski. The poet used a variant for his native city which has known many administrations since it was first established in the 5th century and is currently known as Lviv

It may seem that I am a bit cranky about publishing in the 21st century but I have to say that it’s always the end point in writing for me. I began to write with the sense that the process was complete when the piece found a place in the larger world. I don’t begin a work with any idea of what might happen when I’ve finished, though. Not yet. I live in the language, the world of the writing, and when I come up for air, it’s then that I realize that I have no idea if the work will ever find a readership. I am too many things that are not what the current world wants or needs. Who wants to read about a fishing village or a party under fairy lights in a garden on the edge of the world or eye injury or indigo dye or the musings of an aging grandmother? A woman married for 45 years. I know some people do but maybe not enough of them. Enough of you, I mean. But I have some years left and those will find me at my desk, finding a way to map out the terrain I dream about, yearn for, to find ways to knit together strands of music, roots of family trees, and real trees too, embellished with salmon bones, the beautiful holdfasts of bull kelp and bladderwrack (the tired images scorned by A.F. Moritz all those years ago). There’s a little quote from the writing of the early naturalist and advocate for wilderness, John Muir: “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” I keep this in my mind and heart as a mantra. I don’t know how this might be worked into a synopsis or query letter or proposal but it keeps me anchored, heldfast, to what I want to do in my life. Everything else is a bonus.