“Some days he simply dreamed. Didn’t eat or rise from his bed except to use the toilet. If someone entered the room, he turned to face the other way. He kept his eyes closed and dreamed. It was a long path to dream down, to the past, where he was lithe and loose-limbed, a boy at home in the world. Tom, his father called, Don’t forget the tiller, and he paid attention, on those treacherous waves, murres and puffins with their curious beaks low in the surf, terns and kittiwakes wheeling above the boat.

That trip to Klukwan, how long ago was that, when his father photographed the Whale House, photographed the blankets hung on a line, fine Chilkat blankets of spruce bark and goats’ wool. He saw so clearly the man in the Raven of the Roof hat, the dancers in their Snail House regalia, his father coaxing an acquaintance to act on his behalf to purchase them. He saw the Rain Wall with its hole for the chief to enter his quarters, the Raven Pole (he’d peered into the faces carved in the Raven’s feet), the Black Skin Pole. But the man knew their worth and wouldn’t help. He had other plans. His wife, who spoke no English, glared at Tom’s father and shook her finger fiercely. Still, his father photographed those events – the dances, the potlatches; and somewhere there were prints. The Museum, probably. But he didn’t need to look at them; there were times – this was one of them – when those days were as vivid as light. He walked the grey streets of Klukwan, smoke in each chimney, fish smell rank in the air, watching the sun come up, while his father still slept in the tiny cabin of their boat. The river steamed, full of salmon, and boys as young as himself crouched above them with spears and nets. And sailing back to Juneau, he watched the glacial creeks, dark and silty, swirl into the green water of the fjord. Fountains of water which his father said were humpback whales, so close the spray wet his face like rain.

Some days he dreamed of the War, how he tried to help the horses who screamed in the mud, their guts hanging out, flies already at work, he dreamed his way back to the terrible smell of gangrene and mustard gas. Some days, dreaming, he was already dead, a medic leaning over him and touching his wrist for the pulse; suddenly he sat up, asked for a smoke. For a moment he had entered heaven, then returned to earth, which he’d always regretted.

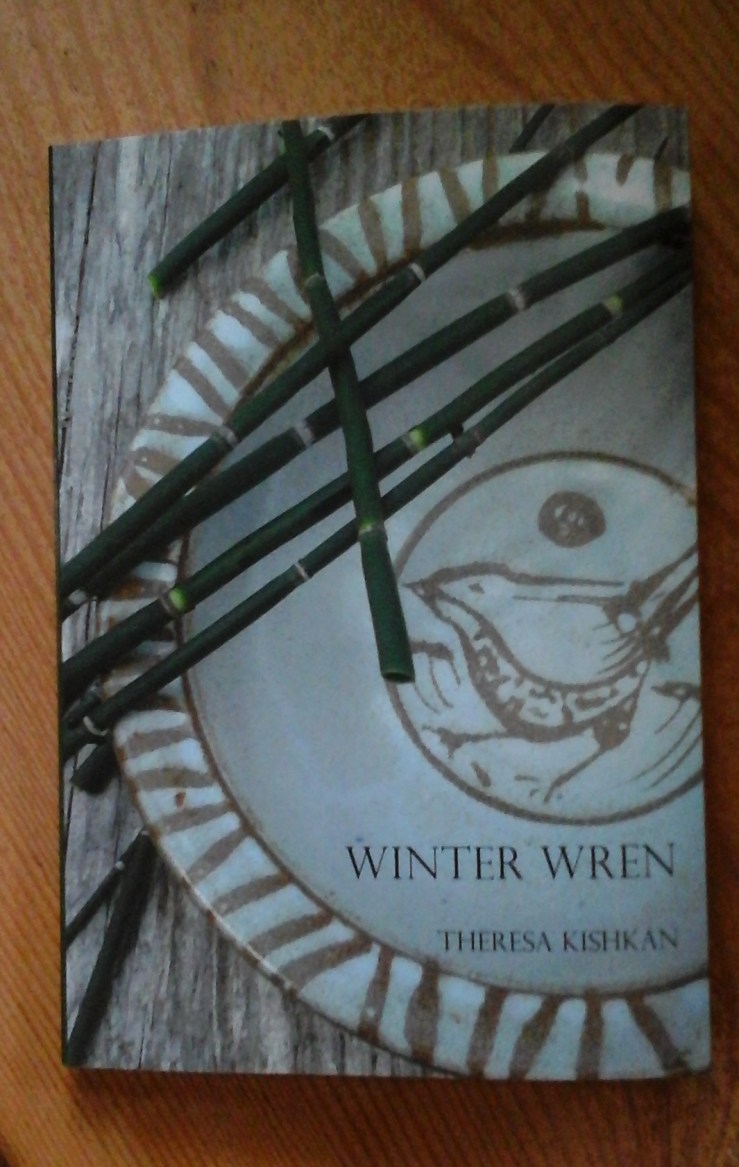

Some days he still sat on the porch above the ocean, a younger man with hands unspotted and strong, looking towards the salal where the little wrens hunted for spiders, rewarding him with their song, as plangent and lovely as anything he heard at the Royal Theatre in the days when he studied violin and thought he might pursue music as an occupation. He tried to capture the notes, the staff hastily drawn onto a blank page and his few years of theory helping him to figure out a time signature, pitch, the run of notes (16ths), a rest, another bar. He heard harmony, almost, the bird its own counterpoint, but realized it was another wren, further away. He was there on that porch at the end of the day, listening and transcribing, when a nurse appeared at his bedside to say that if he didn’t eat, then she would seek a doctor’s order for an IV.”