Tonight is the launch for my novella Patrin. In the way that one does, I’m anticipating questions (not necessarily tonight but in the next while as friends and strangers read this book that takes place partly in the city of my birth and partly in the country of my grandmother’s birth) about the intersection of fact and fiction. Sometimes I write what I call fiction and sometimes I write what is presented as non-fiction. Each is embellished with elements of the other. How could it be otherwise? I think of myself as a writer first, a citizen of language, and sometimes the world is so rich and dense with materials, with possibilities, that I feel dizzy with it. Joyous with it. And sometimes burdened by it.

For the past few years I’ve been working intermittently on pieces which hover between essays and stories. Some are just fragments of dialogue, overheard. Some are lists of findings, catalogues of family details. Some are sustained narratives. One is a wild patchwork of math and botany, genetics and animal behavior. I haven’t worried about the final organization of this material. Yet. But I know that at some point I’ll have to decide what it is.

I’ve been rereading Alice Munro’s The View From Castle Rock. It’s one of my favourites of all her books, though I have to say that on any random day, my favourite might be another book entirely. Maybe I mean that it’s the book that puzzles me and enchants me, in equal measure. Some of it seems to be pure memoir. Sometimes Munro takes a single fragment of factual material and meditates upon it, asking questions of it, giving it a life beyond its immediate presence. She writes, in her Foreward, about the genesis of the book. She tells us that she had been looking at family accounts, letters, recollections:

I put all this material together over the years, and almost without my noticing what was happening, it began to shape itself, here and there, into something like stories. Some characters gave themselves to me in their own words, others rose out of their situations. Their words and my words, a curious re-creation of lives, in a given setting that was as truthful as our notion of the past can every be.

During these years I was also writing a special set of stories. These stories were not included in the books of fiction I put together, at regular intervals. Why not? I felt they didn’t belong. They were not memoirs but they were closer to my own life than the other stories I had written, even in the first person. In other first-person stories I had drawn on personal material, but then I did anything I wanted with this material. Because the chief thing I was doing was making a story. In the stories I hadn’t collected I was not doing exactly that. I doing something closer to what a memoir does — exploring a life, my own life, but not in an austere or rigorously factual way. I put myself in the centre and wrote about that self, as searchingly as I could. But the figures around this self took on their own life and colour and did things they had not done in reality. They joined the Salvation Army, they revealed that they had once lived in Chicago.

I don’t know that any of those surrounding my particular self joined the Salvation Army but there are some individuals and occasions I don’t know enough about and perhaps never will. And maybe it’s time to explore the possibilities of those instead of waiting, waiting, waiting to find out the actual facts which I suspect will never be revealed. The land my grandmother bought near Grays Harbor, Washington, for instance — how did an immigrant woman living in Drumheller, a widow (I think) at that point, with at least 7 children, buy land in Aberdeen? My father told my son that she discovered the property was worthless and she took a shotgun with her to confront the man who sold it to her. Did she get her money back? My father said she shot fish to feed her children. Grays Harbor is a bay composed of many estuaries — the Hoquiam River, the Humptulips River, the Chehalis, all of them salmon-bearing rivers. In those years — this would have been the early 1920s at the latest — I imagine the salmon-runs were the old legendary runs, so many fish you could cross the river by stepping on a living bridge. I can smell those fish, can see that woman with her shotgun and her children. So a story, a fragment, and as mine as anything ever is.

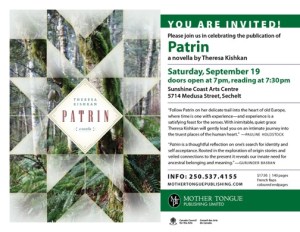

Releasing one book to the world creates such space for the imagination. I have been sorting (in the most chaotic way) some of the material I have in my study and I keep hearing quiet voices. In Patrin, there’s a poem by the wonderful Czech poet Jan Skacel; its opening line is “Don’t fear the voices.” Patrin Szkandery takes the poem and its advice to heart. And maybe it’s time I did too. I look at this photograph, for instance — a baby who would have been my aunt if she’d lived. Julia Kishkan. She died before my father was born and I know almost nothing about her death. This photograph is anything but empty though. Her older (half) sisters, the curtain, the window, the cloth under the casket, and all those brothers and sisters who aren’t in the photograph. Julia’s parents, my grandparents, whom I barely knew but whose lives deserve my attention, now if ever there was a time. “Don’t fear the voices, there’s a lot of them.”