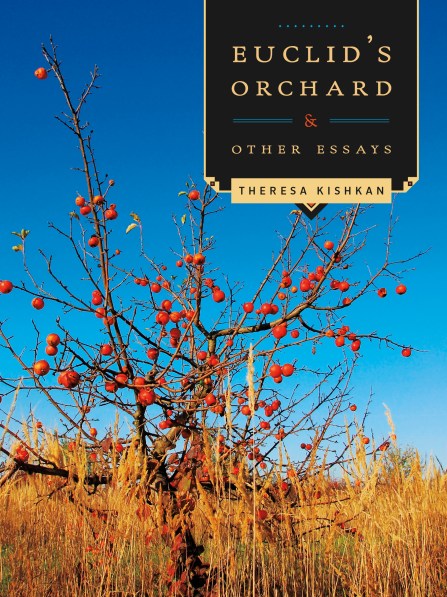

First thing tomorrow, we’re heading off into the wild blue yonder. First stop: Word on the Lake in Salmon Arm for a weekend of readings, workshops, and editorial sessions with aspiring writers. From there, to Edmonton where most of our tribe (we’ll miss Angelica!) is gathering for a week-long building project at Brendan and Cristen’s house. The lumber’s been delivered, the sand for settling foundations, John has filled the trunk of our car with tools (because most mathematicians don’t have power saws, assorted levels, a plumb-bob, crow-bars for prying an old porch off the side of a house, and various other implements collected and used in the long process of building a home here on the Sechelt peninsula). Forrest, Manon, and Arthur are coming from Ottawa so it will be a week of animated conversation, many bottles of wine (we’re bringing some of those too), and, for some, mojitos. I think of cocktails as Mother’s Ruin (it doesn’t take much) so won’t partake* but my contribution will be 2 pots of mint. As I’ve weeded this spring, I’ve kept the volunteer mint to take to Edmonton. Some of it already travelled to Ottawa and is part of a garden there where a small boy will be told one day, “Your grandma brought this and guess where it came from originally?” John’s mother used to visit and in the trunk (or boot, as she called it) would be many cuttings and roots of plants from her garden. I’ve written about this in “Ballast”, one of the essays in Euclid’s Orchard.

She carried rooted shoots of the original family wisteria in turn from her mother’s garden in Suffolk, wrapped in damp paper in her suitcase after one of her annual summer visits to her mum. Have you anything to declare, I imagine her being asked, and like me (who carries acorns and interesting cones and seeds from everywhere I visit), she took a deep breath, keeping inside every important reason for children to continue their parents’ gardens, and said no. In her suitcase, the long roots of her mother’s mint, the perennial geraniums.

And it will be a week of little trips too to places that speak to me — to us — of our family connections. Two springs ago, John, Brendan, baby Kelly, and I drove out to the Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Village, east of Edmonton. I don’t know many details about my grandfather’s life in Bukovyna but somehow seeing the Nazar Yurko house gave me some insights into the domestic culture of his village (Ivankivtsi).

We’re planning to drive out the open-air museum again this trip, with all the grandchildren strapped into their car-seats. They’ll see the house with its adjacent garden, where I remember drifts of ferny dill that the young woman weeding told me self-sowed everywhere. (I wanted to lift a little clump and tuck it into my pack. Maybe this time I’ll be bolder.) They’ll see the church

and I’ll show them a photograph of the church in their great-great-grandfather’s village and they might hear the echoes that I hear when I enter these buildings.

And then their fathers can muddle the mint that came from their great-great-grandmother’s English garden (via their great-grandmother, and then their grandmother) and make a jug of mojitos. So the world is remembered, mint and rum and the bells of old churches.

*I mean cocktails, not wine. I’ll drink more than my share of the Wild Goose Pinot Gris but mixed drinks catch up on me sooner than I’d care to admit.