I’m at work on (yet) another essay about family history and am trying to puzzle through something that is both about place and about the public record. In Euclid’s Orchard, in an essay titled “West of the 4th Meridian: A Libretto for Migrating Voices”, I wrote about my discovery that the homestead I’d believed my grandmother’s first husband had taken out in the Drumheller area prior to her arrival in Canada in 1913 didn’t exist. Instead, she arrived to a squatters community. In spring of 2016 I’d gone to the Provincial Archives in Edmonton to make a copy of a few documents I thought would help me to find the 1/4 section of land I’d always believed my grandmother’s first husband owned and was surprised to find instead the whole long file of maps, letters, petitions, directives, etc. On that day in 2016, I didn’t have time to do anything more than make one or two copies of pages I thought might be useful. Later, my son Forrest sent me a pdf of the microfilm detailing the difficulty the residents of the community had in petitioning the federal government for permission to buy the individual plots they’d settled on. Instead of a copy of the homestead grant and a map, I had 398 pages to decode and try to understand. I don’t believe that my grandmother and her first husband bought the plot they were living on when a portion of the land was subdivided in 1918. Their names don’t show up on the list of purchasers and anyway in 1918 that husband died in the Spanish flu epidemic and my grandmother had a new baby, her 9th, who was to die just a few months later.

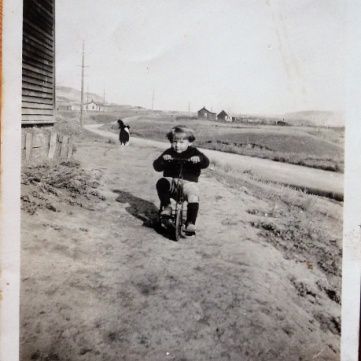

In 1920 my grandmother remarried. She married my grandfather John Kishkan. They show up on the 1921 Census (though I didn’t find them at first because my grandfather’s surname was misspelled) and again in 1926, living on the north side of the river, near the Midland Mine. I suspect my grandfather worked there. A few weeks ago in Drumheller, John and I took the two photographs we have of my father as a child and tried to find the location of the small farm he lived on by matching the hills in the photographs with the hills near Michichi Creek above the Dinosaur Trail, formerly Midland Road (the address given on the Census forms). That process is what I’m writing about now.

It gets complicated and in many ways it’s a useless exercise. What can I possibly learn by looking at striated hills and barren ground? Maybe something. I’ve discovered that the actual section of land where the squatters community was and where my grandparents had their farm is the same. The records are confusing. It was School Land. It was owned by someone called James Edward Trumble and maybe it was owned by someone else. Maybe my grandparents owned a little piece. Or maybe they rented a piece. I hope to figure it out.

On this map (which asks to be a quilt, doesn’t it?), you can see Range 20 on both sides of the Red Deer River.

Imagine the small farm tucked against the flank of hill. Imagine waking to the striations, walking out to the morning in the shadow of those layers. My father once wrote a letter to me when I was living in Ireland, so it must have been 1978, and he mentioned he’d been to the funeral of his last living (half)brother, Paul Yopek. He’d driven to Drumheller after that funeral and wrote that he saw the hills where he’d walked as a boy but had never found anything worth keeping in his life. I thought he meant fossils but perhaps his comment was more ontological. Looking at the sedimentary layers exposed by weather, the mudstone, sandstone, the coal seams, and shale, all softly coloured and shimmering in the light, I wondered if they might take up a large space in the physical topography of a boy growing in their shadows. Paleontologists were at work in the 1930s when my father was a boy and perhaps he encountered one on his forays into the hills. Maybe he’d been asked to keep his eyes open and maybe he had and nothing ever showed up. The long rib of a creature as old as time. An ammonite. A nest of fossilized eggs. In his rough house, his mother made noodles, his father came home dark with coal dust.

— from a work-in-progress