Yesterday I swam in the local pool for the first time since early May. I’d been in the lake the day before and knew that it would be my last day. It’s not so much that the water is cold, though it’s certainly chilly. It’s more that the air is cool and I can’t get warm afterwards. Even wrapped in a big towel as soon as I get out of the water and even after a hot bath. Someone suggested a wetsuit but somehow that’s not how I want to swim, though I know it works for others. I want the water to polish my skin. And the pool is a good compromise, even if it’s loud (or was yesterday as the children from several families shrieked and whooped, a good sound for the most part) and crowded enough that John and I had to share the one lane roped off from the rest of the pool. You can’t enter that meditative state if you’re trying not to bash your partner with your arms as you back-stroke down the pool. The lane was not quite wide enough for two.

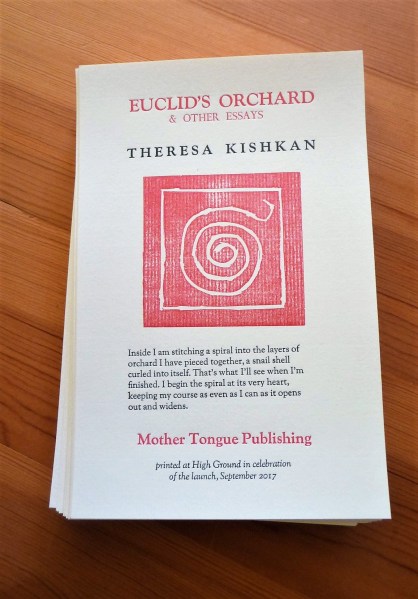

But luckily I’ve begun a new single-cloth quilt, some of the ecru linen I twisted and tied with hemp string and then dyed with indigo and rose madder. (You can see both of the lengths at the top of this page.) I threaded 3 sharp Japanese needles with blue sashiko thread and fitted the fabric into a frame. Then what. I looked at the watery pattern of the dye and began to sew a spiral. It will morph into something else and I’ll probably do what I’ve begun to think of as form of punctuation: ending a long line with a small akoya shell button.

Behind the frame is another single-cloth quilt made of white linen dyed with indigo. The colour is quite different. The process is always interesting because I think I’m being honest when I say that I don’t really care about results; it’s what happens as I twist and tie scoured fabric, as I prepare the dye vat set up on a long cedar bench out by my vegetable garden, as I dip the lengths into the vat and then remove them to oxidize, watching the swampy colour turn the most beautiful blue.

With the rose madder, it’s not quite the same. The fabric has to simmer in a mordant, then soak in a big pot of prepared dye on the little hotplate I have set up in my outdoor dye workshop.

But when the dye has done its work and I unwrap the fabric, it’s like a gift. A birth. And as I sew, I’m thinking about a show I’ve learned about in London, which we will go to when we’re there in late October. Yto Barrada’s work sounds so congenial. (And what’s so interesting is learning that she has a property with arts residencies in Tangier, the Mothership, with a dye garden and workshops, and oh, of course I’ve been dreaming as I sew.)

There is a relationship between what happens when I swim and when I stitch. The two of them locate me in my body as well as elsewhere, a spirit realm, a cloudscape. When I swam all summer under blue skies, scraps of clouds drifting overhead, I was part of what was happening. And when I run my sharp needles through the dyed linen, I am making a veil, I am drawing together a seam of water, of sky, of self.

This is love: to fly toward a secret sky,

to cause a hundred veils to fall each moment.

–Rumi