It’s my daughter Angelica’s 30th birthday today. I was 30 when I gave birth to her, our last child. My memories of that autumn are happy ones. I’d bathe her in a plastic tub on the dining table with sunlight streaming in the big window. She loved her father to hold her on his stomach as he watched television — he’d pat her back and sing little songs to her. And her brothers were fascinated by her and quite impressed that she knew them well enough to bring them a special gift home from the hospital — a Playmobil gas station, complete with tiny parts that all had to be assembled in secret by parents and grandparents late into the night before they discovered it the next morning.

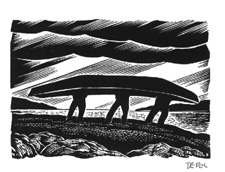

Having a daughter has been one of the great pleasures of my life (as is having sons, but the pleasures are different, something I’ll try to analyze another time). I’ve had access to a thread that runs from girlhood to womanhood and back. As a writer this has been so valuable. When I was writing my first novel, Sisters of Grass, Angelica was about ten. And when it was finally published, she was 16, nearly the age of the novel’s protagonist Margaret Stuart, who is a young woman living in the Nicola Valley in 1906. That period intrigued me — so much of the valley still retains traces of that time: names on gravestones, old buildings, a legacy of ranches and settlement. And Margaret Stuart is in turn fascinated with the cist burials she finds evidence of on the Douglas Plateau, particularly an incised bone drinking tube which would have been buried with a pubescent girl for her afterlife. Our family camped in the valley in those years and I felt as though I was seeing the world through a series of shifting transparencies, shapes visible now, and now, and now, and then fading as something else replaced them for a time. I know now that this was the awakening of the part of my imagination that allows me to write fiction but then I was in a constant state of wonder.

In the epilogue to the novel, I meditate on memory and the apprehension of those transparencies:

What secrets do the hills contain in their suede hollows, what mysteries are lifted from the stones in the unbearable stillness of morning? Which is the way where light dwelleth?and as for darkness, where is the place thereof? My daughter has rolled into the grassy hollow of the kikuli pit at Nicola Lake, closing her eyes as she imagines the life of its ghostly household in the time we nearly know as we sit on the shore of the lake. Looking up, she sees a fresh moon in the daylight sky, hears the girls singing wherever they might be — in memory, in photographs, crumbling bones under a cairn of boulders, a little necklace of elk teeth at what was once a youthful throat, in the heart, the imagination. You remind me a girl I once watched picking flowers. On the shoulders of the young girls, golden pollen; in their hair, a halo of seeds, ruffled by the breeze. If we are very quiet, they might sing to us, dry husks in the wind, dust of stars.

That line from Sappho is something I’d like to say to my daughter now. You remind me of a girl I once watched picking flowers. And here’s a bouquet of late “Mme. Alfred Carriere” roses, as sweetly scented as anything on earth, to say Happy Birthday, Angelica!