As we were lying in bed on New Year’s Day, John said, I fell asleep in one year and woke in another. And I felt the strangeness of this, felt suspended in time’s uncertainty. Maybe this has always been my true state. I began the new year by working on my novel-in-progress, Easthope, set about ten years ago in a small coastal village. For a number of reasons, the main character feels the same: suspended. I spent some time looking at photographs of old Easthope marine engines. A year or so ago, a friend showed me through his late uncle’s collection, housed in a shed on Francis Peninsula. His uncle must have felt the urgency that I feel, to care for and keep alive things that have been important to the way people have lived. These Easthope engines powered coastal fishing boats from about the turn of the 20th century into the 1950s. They changed the way people fished, particularly the more reliable 4-cycle model which pretty much replaced the original 2-cycle design. My friend showed me many Easthopes and the diesel Vivians. I loved their sturdy beauty. I loved the shed, a museum of the useful past, with its springboards, a box of piano rolls, tools, and cans of grease.

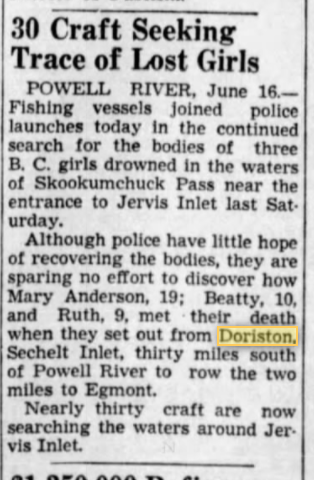

Some days I feel as though I fell asleep in one century and woke in another. I drift between them. My own desk is a museum, the books lined up at the back relics of another time: Fowler’s Modern English Usage, Gary Snyder’s Axe Handles, Raincoast Place Names, a concordance to the Bible. I hold papers down with fossils from the Great Salt Lake and the Sooke Formation, stop to fit my late dog Lily’s pelvis back together (it cracked into 3 pieces when a shelf fell onto my desk, something I wrote about in “A Dark Path”), look at the 5 tiny hummingbird feathers in a jam jar. Asleep in a century I am unwilling to give up, as the character in Easthope is unwilling to leave aside a story she’s discovered about children drowned in the Skookumchuck Rapids as they tried to row from Doriston to the Egmont dock. On a grey morning, this grey morning, I can almost hear the put-put of Easthopes in the Strait, can almost smell the nets drying. A rock heavy with fossil corals is holding a book open to a poem that is keeping me company today, “Winter Brothers’, from Charles Lillard’s Shadow Weather:

There should be no poets, only a few poems,

winter brothers,

travelling as well as Irish whisky,

a ketch-rigged dory

and old friends

shaking off women, fish and certain anecdotes

to beat along my tack north.

If Charles was still alive, maybe we’d talk on the phone. Happy New Year, I’d say, and he’d ask what I was working on, and I’d tell him about Doriston and the sisters who drowned. I’d tell him about the Easthopes. A day or two later, I’d get a call from the man who used to own the gas station at Garden Bay Road, telling me a parcel had arrived for me by bus from Victoria. When I opened the parcel, it would be an archive of the old coast: pamphlets, brochures advertising Easthopes and Vivians, articles clipped from ancient newspapers describing bad storms, the coming war, a tragic accident in Jervis Inlet. By the fire where I’m going to go now to drink my coffee and warm up, I’d look at every page, and for a moment the novel would be clear in my imagination, clear as deep water, salty and wild.

Clear in my imagination, and now the long winter to get it down, make it right, find out how all the pieces fit. One piece? The lights of a small boat leaving the dock as we ate dinner at the Backeddy Pub last week, lights that flickered into the darkness, and then disappeared.

I’m just about off the map.

It ends over there in a cluster of islands

and a swale of sandpipers.

Note: the passages of poetry are from Shadow Weather: Poems Selected and New, by Charles Lillard, published by Sono Nis Press in 1996.