Yesterday, swimming, I wondered how many days I could continue. John has begun to swim in the local pool and soon I’ll join him but I’m not ready to give the lake up just yet. Just yet. Though the water is very cool, I have to say, and there are moments when I can’t feel my toes. What I don’t want to give up: the kingfishers, the quiet, the muffled cloud over the other shore, the trout jumping for insects, how it feels to glide through the green water, eyes closed. I don’t think I’ve ever felt so alive as I do on these mornings. But one day, not this one, I will wake and think, No, it’s just too cold. As it is, John sits in a folding chair under the big fir in three layers, with gloves on. When I get out of the water, he holds my big towel so I can wrap up. I’ve been in the lake each day since May 19th, with a little break to go to the Island for Angelica and Karna’s wedding.

Last night I was awake for hours, thinking about the chaos of the world right now. How far we are from the civility I believe we are capable of. In the night the situation(s) felt perilous–and I don’t think that’s an exaggeration. I’d been reading a book before sleep, by flashlight because the power had gone out in our first autumn storm, and I didn’t want it to end. Gumboot Girls, a gathering of stories and recollections of women who’d arrived at Prince Rupert and Haida Gwaii in the 1970s to make new lives for themselves. They built houses, learned midwifery, grew food, towed logs to beaches to cut into firewood, canned salmon and clams, learned to dress venison, to smoke fish, make cheese from goats milk. One of them, Chloe Beam, wrote about going up the Skeena River in her skiff to pick up a box of tiny chicks in Terrace. She was also the woman who wrote so beautifully of wolves, a song I’ve heard in the early morning once or twice:

I stepped outside on the dock this particular night. I was astounded by the brightness. I looked up and behind undulating dripping curtains of aurora borealis filling the entire sky. I had just seated myself on the rocks of the point to enjoy the electromagnetic spectacle, when from the next point over, a pack of wolves started to howl. At first it was intermittent. Then the wolves got into full swing. They bayed and chorused, sometimes in unison, sometimes in solo arias, calling down the northern lights to dance and snap in rhythm.

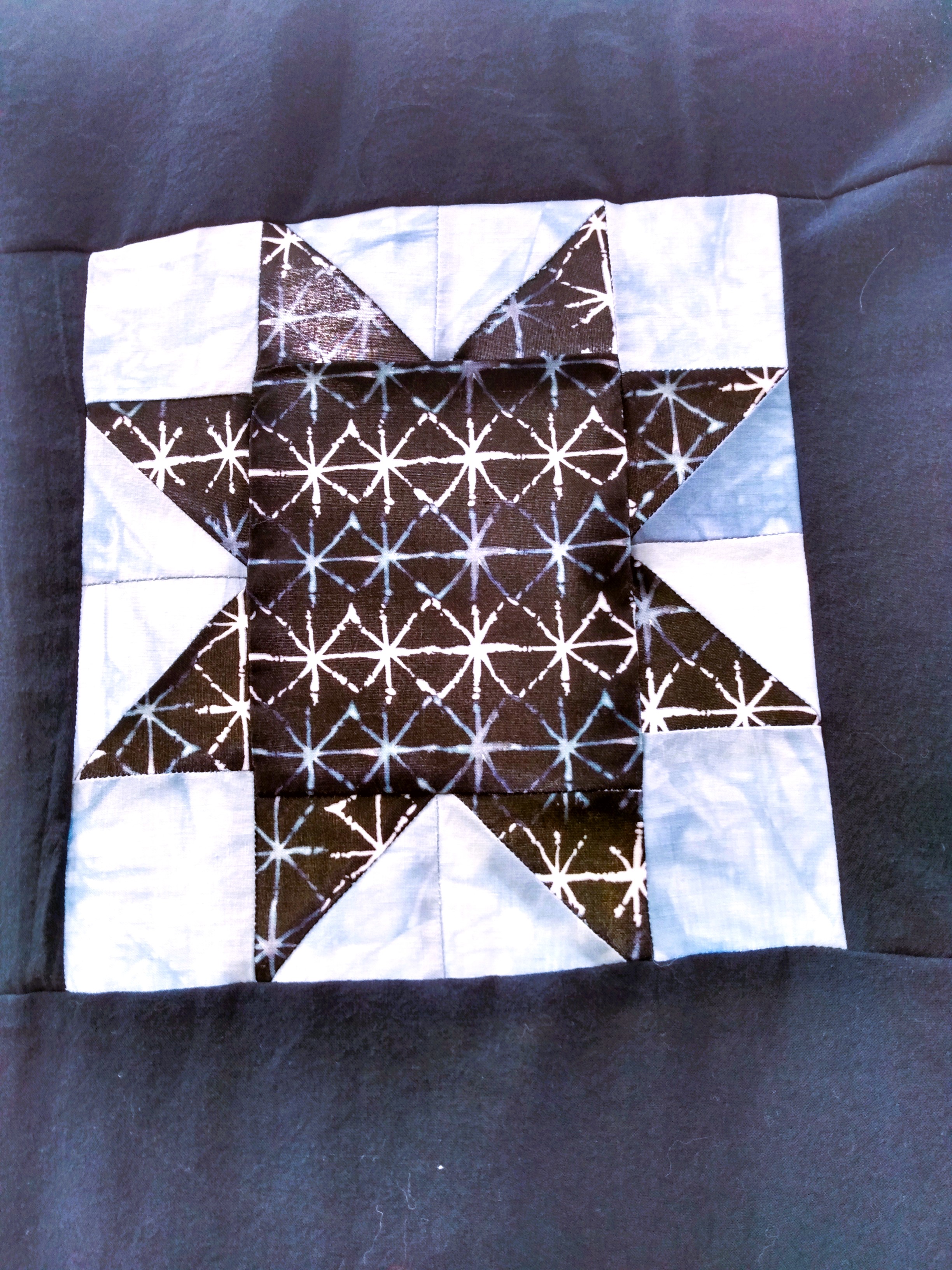

So one world, the one that feels upended and troubling, and the other world, where women cut wood with a swede saw, tend babies next to tin stoves, make quilts together, held in a kind of uneasy balance. Part of the uneasy balance is closer to home. Yesterday I was shopping in Sechelt when a woman asked me if I’d heard about the grizzly seen on the beach that morning. The beach where I gather the stones to tie into linen for indigo dye work, where my grandchildren love to swim in the summers and explore the tidepools at low tide. The beach right in front of the condominiums, one hotel,the walkway usually lively with bikes, dogs, little kids on scooters, leading to the play park. This beach:

No, I said, I hadn’t heard. She said the RCMP and the conservation officers were at Chapman Creek where the bear had walked to along the beach (Chapman Creek is a salmon stream). And later I learned that the bear had been trapped and relocated. But grizzly bears are so rare in our area, almost always young ones who’ve somehow arrived by water –one swam Jervis Inlet to terrorize pigs in Egmont about 8 years ago– or across the ridge from Salmon Inlet to explore Gibsons. I’ve only seen one, and not here; in April, at the head of Bute Inlet, watching guys unload a tanker truck full of 70,000 Chinook salmon smolts to be released in the Southgate River, we were alerted to a grizzly bear at the Homathko River estuary, just on the other side of the inlet. It was leisurely grazing seaweed (it looked like), raising its huge head occasionally to look our way. We don’t often get to see something so completely wild and beautiful. Though three days ago I was at my desk when I saw the grape vines moving around a corner of the house just beyond my window and when I went upstairs to see what was going on, I saw two black bear cubs, this year’s, scrambling across the upper deck to the stairs leading down. No doubt their mum had alerted them to the possibility of grapes–bears have very sophisticated memory maps of food sources– though ours had been picked and they were out of luck.

When I swim later this morning, after John returns from the pool, I’ll be thinking about bears and our planet, and the shifts and dangers of being alive at this time in history. I want to believe we can do the right thing, as a species, as citizens, and that our precarious arrangements, social, political, ethical, and ecological, can somehow be brought into a healthier balance. I hope the bears can find a balance too that doesn’t require them to graze on seaweed on the beach of a small town on the Sechelt Peninsula because these stories seldom end well for them. When I swim, I’ll remember the bear prints I sometimes find in the sand at the edge of the lake and Gary Snyder’s lines for bears.

A bear down under the cliff.

She is eating huckleberries.

They are ripe now

Soon it will snow, and she

Or maybe he, will crawl into a hole

And sleep.