A new century, the first decade

When I’d finished writing Sisters of Grass, I didn’t know quite what to do. The publisher of Red Laredo Boots felt it was between readerships—teen and adult. I sent to a couple of the bigger publishing houses and had quick rejections, one editor telling me that I was simply not ready for Harper Collins yet. Sometimes, looking for something else, I find an old notebook with lists I’d made of publishers sent to and their response. 20 rejections. Or 25. Some silences, though fewer of those in the beginning than now. The current fashion seems to be to tell writers that if they don’t hear within 3 months, or 6, to consider the manuscript has been rejected. This seems like such an abrogation of common courtesy. An email takes a few minutes. Surely we deserve at least this? I thought I’d try to find a literary agent who might be able to represent me because I wasn’t– I’m still not—a very good advocate for my own work. Several rejected me outright but one wondered if she was right in assuming that my name was First Nations, in which case she thought she could do something with my book. I didn’t pursue that. I packaged up the manuscript and sent it to several smaller publishers. I remember receiving an email from Laurel Boone, who was then fiction editor at Goose Lane Editions, telling me that there were many things she liked about the novel but that she felt there were missed opportunities with the two narrative perspectives, and if I agreed with her and made some revisions, she would be happy to look at the manuscript again. Sometimes an editor’s comments make no sense but hers struck a chord and I opened a new file, inspired again by Jack Hodgins, and retyped, added a formal dimension to both separate and connect the two narratives. When I’d finished, I sent Laurel the manuscript and she immediately accepted it with such enthusiasm that I floated through the next few days. Working with her and the team at Goose Lane was wonderful. I loved Julie Scriver’s cover design. And when Susanne Alexander phoned to say that they would be interested in another book, I told her about Inishbream. Although of course it had been published the year before, the print run was very small and all copies were quickly sold. At that time, Goose Lane published novellas in a small format ideally suited to the form and after discussion with the Barbarian Press, Inishbream was accepted, along with some of John DePol’s images for the cover and frontispiece.

Kishkan’s prose is clearly that of a poet, but it’s restrained in service to the narrative – rich and evocative, but never overwrought. Sisters of Grass is beautifully understated, with a quiet grace that succeeds in transforming the regional to the universal, filling the reader with a sense of the mysteries of the world, and humanity, that can never fully be resolved. (Robert Wiersema, Quill and Quire)

Interesting and unexpected things happened, maybe the sweetest being the man who owned the bookstore in Merritt telling me (after my children held up my book in the store and told him I’d written it) that people all over the Nicola Valley were impressed that I’d got the lineages of the horses right! I was invited to several festivals after Sisters of Grass and Inishbream were published. I remember sitting at the book table at the Vancouver Festival of Writers and having a BC publisher introduce himself. He wondered if I might be interested in publishing a collection of essays with his press. I didn’t think I had enough essays but he followed up and I realized I did. I was also finishing another novel, A Man In A Distant Field, which I’d begun after a conversation with two men in my community, one a fisherman my own age and one much older. The older man was describing what it had been like to come up to Pender Harbour as a child, in a storm, on a boat carrying seed oysters, and how his father had tied him to the gunwales so he wouldn’t wash away. I felt an intense shimmer, that’s the only word I can think of, as the story settled into my imagination. A few nights before the conversation I’d dreamed of a man curled up in the bottom of a Columbia gillnetter, the craft drifting to rest on a shore, and the two strands came together in my consciousness, turning and twining, and I wrote myself into a story echoing the middle books of the Odyssey, a poem I’ve loved since I was an undergraduate, 50 years ago. I thought I’d try again to find an agent. I wondered if I might be doing my books a disservice by not pursuing possibilities that arose: a film query, foreign sales. I did enter into a relationship with a woman who read my new manuscript, signed me, and then kept telling me the book wasn’t quite ready to send around. After a year of this, without any clear direction, she told me she’d had a brainwave: I could rewrite my novel as a sort of modern retelling of the Odyssey! I gently responded that the ancient and beautiful poem already anchored much of my narrative, the relationships subtle and implied, and I wasn’t interested in an obvious scene-for-scene equivalency. And I realized that as much as I liked her, she wasn’t going to do anything for me that I couldn’t do myself.

That book found a publisher, Dundurn, and came out in 2004, receiving a nomination for the Ethel Wilson Prize. It was also a book that inspired two generous readers to pursue possible film interest on my behalf. Nothing came of it but I was grateful for their efforts. And who knows, the novel still exists and maybe it would make a good film. I only wish Daniel Day Lewis was still considering roles.

Kishkan carries all this off masterfully in a scant 300 pages by combining the crafts of the poet and the screenwriter. There isn’t a moment in this novel when you can’t “see” something intensely, whether it’s the shining black dorsals of a pod of killer whales shadowing a cedar canoe or the wildflowers growing around a secret “Mass stone” where Irish Catholics were driven to take the sacraments in the wilds. The cadences of Irish speech, not only in the dialogue but subtly woven into the narrative, maintain the continuity of Declan O’Malley’s mood, as well as a sense of the period. Kishkan also uses a technique from classical Greek drama. A powerful sense of horrific violence informs the story, but the violent events all occur “offstage,” recounted in dialogue or as memory flashbacks. The only one that forms part of the action is the aftermath of a beating. (John Moore in the Vancouver Sun)

Oh, and that publisher who asked for the essay collection? I put one together, he accepted it, I signed a contract, received a small advance, his designer made a beautiful cover using a friend’s photograph, he advertised it in the catalogue as Forthcoming; as I waited for the edited copy, his publicist set up a book launch, and two weeks before it was to happen, after invitations had been sent out but I still hadn’t had edited copy or proofs, I read the writing on the wall, as they say, and realized the book wasn’t going to come out. My emails went unanswered. I waited until the next catalogue came out with my book listed as Recently Published and with some advice from a lawyer friend, I sent a registered letter cancelling our contract. It was a time when small publishers were experiencing difficulty and I was not unsympathetic but I also didn’t want my name to be associated with shady practises. I remember unexpectedly encountering one of the Literary Press Group sales representatives in a book store and his first words were, “Everyone is asking what happened!”

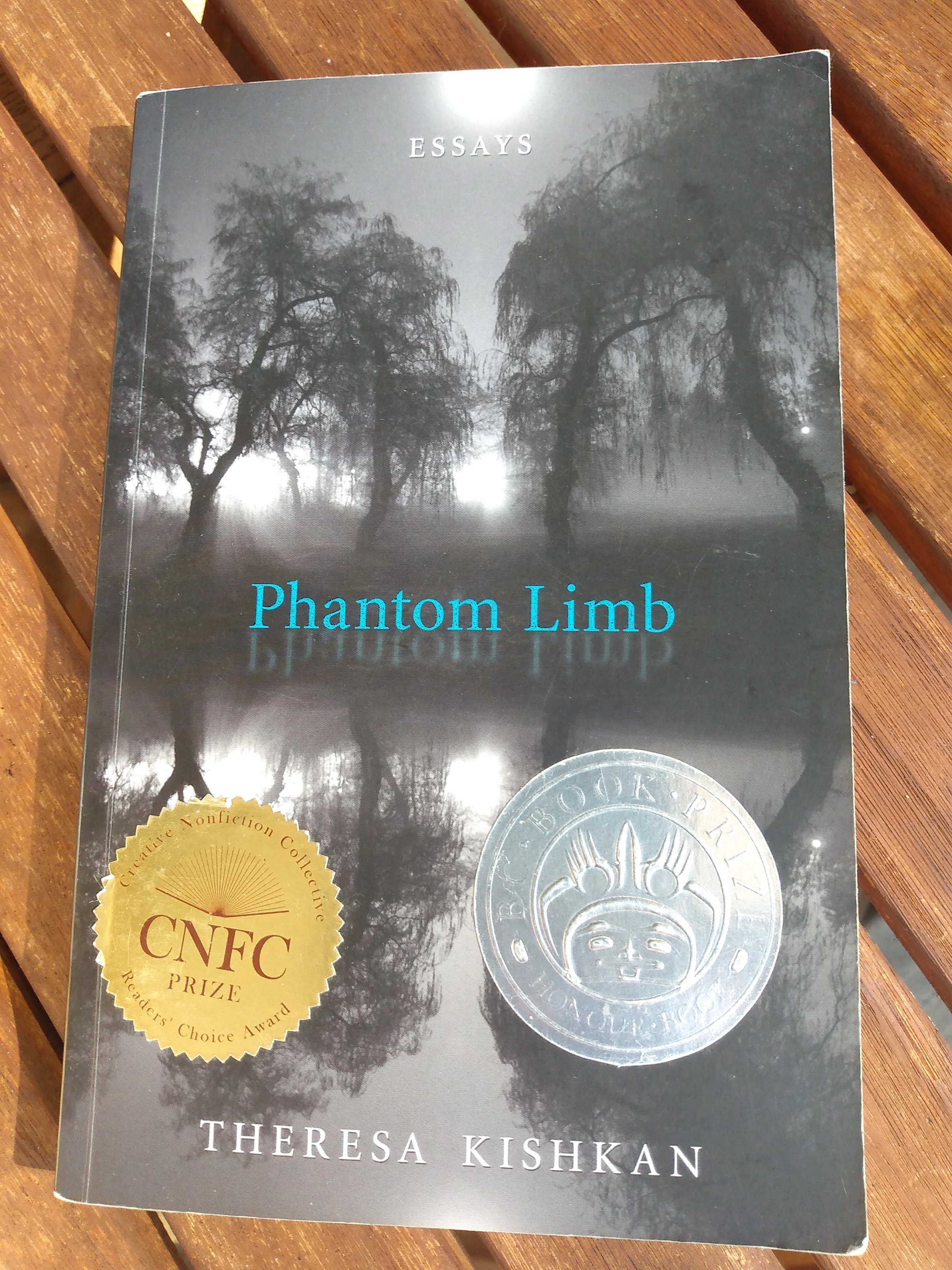

That book, Phantom Limb, found another publisher, Thistledown Press, and my friend let us use another of her photographs. Apart from a small tussle with the editor over my use of the c word – I finally agreed to replace it with “vulva”, a compromise for both of us—the editing was intense and respectful. The book was shortlisted for the Hubert Evans Award for Nonfiction in 2008 and received the Creative Nonfiction Collective’s inaugural Readers’ Choice Award.

Who knows where a book comes from in a writer’s hoard of memory and possible investigations. When I was spending a fair bit of time with aging parents, talking about a beloved family home near the Ross Bay Cemetery, I realized, so late, too late, that the elderly neighbours my mother befriended and offered her children to for errands, well, I realized that a couple of them were Great War widows. The photographs on their mantle-pieces, the quiet beyond quiet in their tidy homes—they represented a legacy I couldn’t have understood at the age of 6 but in around 2005, I began to try. I also realized that a man who used to come out from his long driveway with his spinster daughter, he with a shooting stick, and her with a strange crocheted hat—this was in the neighbourhood my father retired to, in Royal Oak, then still quite rural—and asked me to stop with my horse so the man could stroke his neck, were both notes in the history I was trying to examine in the novel I’d begun. He was Bert Footner, the architect of many of Walhachin’s colonial bungalows, and the daughter was Mollie, born and raised in Walhachin, a place central to my book. I wish I’d known then about Walhachin, though I could have known if I’d paid more attention to my father’s frequent discourses on family trips. Children, he’d say as we drove the Trans-Canada Highway between Cache Creek and Kamloops on our way to his family in Edmonton, there’s the remnants of Walhachin! He pointed vaguely to what looked like a few houses above the Thompson River, some remnants of wooden irrigation flumes, and it wasn’t until I was an adult, driving the same highway with my own children, that it occurred to me to turn off onto the gravel road and see what was left. The book I was writing became The Age of Water Lilies and again, it had a long road itself to publication. Those lists again! 24 rejections for this one. The Age of Water Lilies was published in 2009 by Brindle & Glass. One of the nicest things that happened was that I was invited to be part of International Women’s Day celebrations in the Soldiers Memorial Hall in Walhachin and slept in the old post-office, really a shed used as guest quarters by the woman who’d invited me. Her grandparents had been part of the second wave of settlers to the community, the ones who came during hard times in the 1930s. There was no electricity or plumbing in the little shed, and I got up in the night to pee under a star-filled sky while coyotes sang quite near. I remember that Gordon Parke of the Upper Hat Creek Valley, whose family had ranched in the Valley, as well as on the lower Bonaparte River, came to my reading and he told me I got the details right. I carried his durable praise for months.

The title of this series of histories promises asides and here’s one: I always sent new manuscripts to previous publishers. Sometimes there was a contractual requirement to do this but it also felt like a courtesy. So if you’re wondering why I didn’t simply stick with one publisher, it’s because none of them wanted to stick with me. Maybe they had expectations that my books (or me) didn’t rise to. I don’t think I’m a diva. I enter the editing process respectfully and I meet deadlines. I do my part. I know that Sisters of Grass sold very well, had excellent reviews, and I still receive royalties. But Laurel Boone retired and the new fiction editor had other writers she wanted to work with. I have to admit that I wish for a publisher who would stay with me but as I approach 70, I think it’s unlikely it will happen.

In the first decade of the 21st century, I published 4 books and I wrote another, Mnemonic: A Book of Trees, which came out in 2011. That one is a kind of hinge in my writing life and in the way I see some changes in publishing. I received a phone call from an editor mid-decade. She wondered if there was a book I was interested in writing because she professed to love my work and wanted to guide something of mine through the channels of the company she worked for. I told her I had some ideas for a memoir and we talked at length about it. She suggested I send her a proposal which she would share with the publisher. I thought at length and submitted something. Next I received a call from the publisher, suggesting we meet for lunch. This was in Vancouver. He was very kind and had some ideas for improving my proposal, requiring it to tick a bunch of boxes. He sent me samples of killer proposals, some he’d been able to snap up and publish, others he couldn’t (because others were interested too and offered more money). I remember I came back from the lunch and talked to John about the whole thing. I remember he listened and then he asked, Is this something you actually want to do? It was a proposal, after all, not creative work. I thought and thought about it. No, I didn’t want to “make” a book with constant guidance and editorial shaping as we went along. Because that’s in truth what was being suggested and offered. My writing, their market sense. I need to say that I understand that and I read books all the time that are “made” that way and I enjoy many of them. There’s a logic for certain books: cookbooks, field guides, how-to books, scholarly studies, and so on. I know publishers need to be financially secure and many writers need to write books that are carefully adapted to markets and trends. But it’s not my modus operandi. I wonder when this became the model for the writer-publisher relationship? I see advertisements for courses that teach a writer how to write a synopsis, a proposal, a query letter. On social media, people post updates on the progress they are making with the description of their book. About 5 years ago I was finishing a collection of essays (more on this in the 3rd instalment) and I thought I’d try, once again, to interest an agent in the book. One had been circling me a little on social media and had said some nice things about my work. I sent that person a detailed description of the manuscript, knowing that they had already read one of the essays, published in Brick– a fulsome comment had been made. A response came the next day, suggesting that I visit the area of the agency’s website describing how to submit a proposal. I admit to being somewhat blindsided because I thought this was something that could be discussed over the phone or via email if the agent was interested in the description and other information I’d provided. Did I really need a proposal for a book that was already written? But the new gates, the new gatekeepers! Some of us who came of age as writers in the last century can’t find our way through.

I thought and thought about what and how I wanted to write about my life and as I began essays that I knew would accumulate and talk to one another and share common nodes, I realized I was writing a kind of literary arboretum. (In another life I’d have been a botanist.) I’d grown up among trees, influenced by them, shaded by them, given sustenance figurative and literally by them, and so I followed the trail leading into forests, orchards, lumber yards (an important part of the section about building a house with John), mythologies, and family relationships. I thought about the architecture of memory, of love, and when I was finished, I had Mnemonic: A Book of Trees, a book-length grove of connected essays. I offered it first to the publisher who’d taken me to lunch. He said nice things but ultimately it wasn’t for him. And then I began sending it out. Many of the individual essays had been published, one of them won the New Quarterly’s Edna Staebler Personal Essay Contest, one of them appeared in a journal in the Czech Republic focused on the work of scholars and others (I am definitely one of the others) who participated in a conference in Brno in 2010. As the year turned into the next one, the manuscript was taken by Goose Lane Editions and published in early fall of 2011.

The essay reaches its fullest flower in mature hands. Kishkan’s are practiced and confident, and her prose, while fresh and smooth, also accommodates the knottiness of genuine thought. Mnemonic may seem an easy read, but it richly rewards revisiting. If this book were a tree, it would have deep and thirsty roots; broad and elegant branches; its leaves would always be tipping toward the light; and its fruit would be tangy and sweet. (Susan Olding, The Malahat Review)

The next spring John and I were back in the CR, teaching a course in Brno and giving readings around the country. On our final night in Brno, he received an email from his publisher to tell him that his latest poetry book, crawlspace, had just been shortlisted for the Dorothy Livesay Prize (which it subsequently won). We celebrated that evening with friends over a delicious Czech dinner. Ok, I admit I was a little disappointed not to have received a similar message about Mnemonic but when we arrived in London the next afternoon, there was an email waiting from Goose Lane to say my book my shortlisted for the Hubert Evans Award. I remember we toasted our luck in a Greek restaurant in Bloomsbury where we were staying. And no, I didn’t win that one, though a book about trees did win, published by the man who’d taken me to lunch.

to be continued…