the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s

Now that I am approaching 70, I am going to take some time to set down details, histories, if for no other reason than to leave a record. One of these histories, one that I find myself increasingly interested in, is my own publishing history. Such as it is. It’s a tale that spans two centuries. Two, no, three technologies. And it recognizes some shifts in both the writing life and the publishing industry. Some of them are ones I can adapt to and embrace. Some of them feel alienating. I joke that I’m aging out of the system but maybe it’s actually the truth.

I began to write in a serious and committed way when I was 20, although I can’t really remember a time when I didn’t try to puzzle my way through things in my life with words. When I was around 10, I remember feeling such an intense drive to record how I felt on the long summer days in the neighbourhood my family lived in near the Gorge in Victoria. I’d walk or ride my bike to the public dock at Gorge Narrows near the foot of Tillicum Road, I’d explore Colquitz Creek, and on Saturdays I’d take 2 buses to the Victoria Riding Academy on Cedar Hill X Road to spend the day. An hour of that day was a riding lesson but I also cleaned stalls, swept the barn, helped to feed the horses whose faces I loved, whose flanks I brushed, whose feet I cleaned with a hoof pick. I wanted to write about this and made paragraph after paragraph on lined paper left over from the school term and then stopped, because I realized I didn’t have an idea of how to shape my feelings into something coherent. I don’t believe I ever really stopped trying, though, and by the time I was 19 or 20, I’d figured out, by reading, something about form. When I was in grade 11, a supportive teacher loaned me books to read. You’ll like this, he promised, handing me Seamus Heaney’s Death of a Naturalist or Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. I don’t think I noticed that one book was poetry and the other prose. Under my teacher’s guidance, I wrote constantly and without my knowing, he submitted one of my poems to a national student anthology. It was accepted and eventually (though much delayed; keep this in mind because it’s a common note in my publishing history) the anthology came out. I remember my teacher coming to my home and telling me and my baffled parents that my poem had been cited by the judges as one of their favourites. The judges? I don’t remember all of them but Leonard Cohen was one.

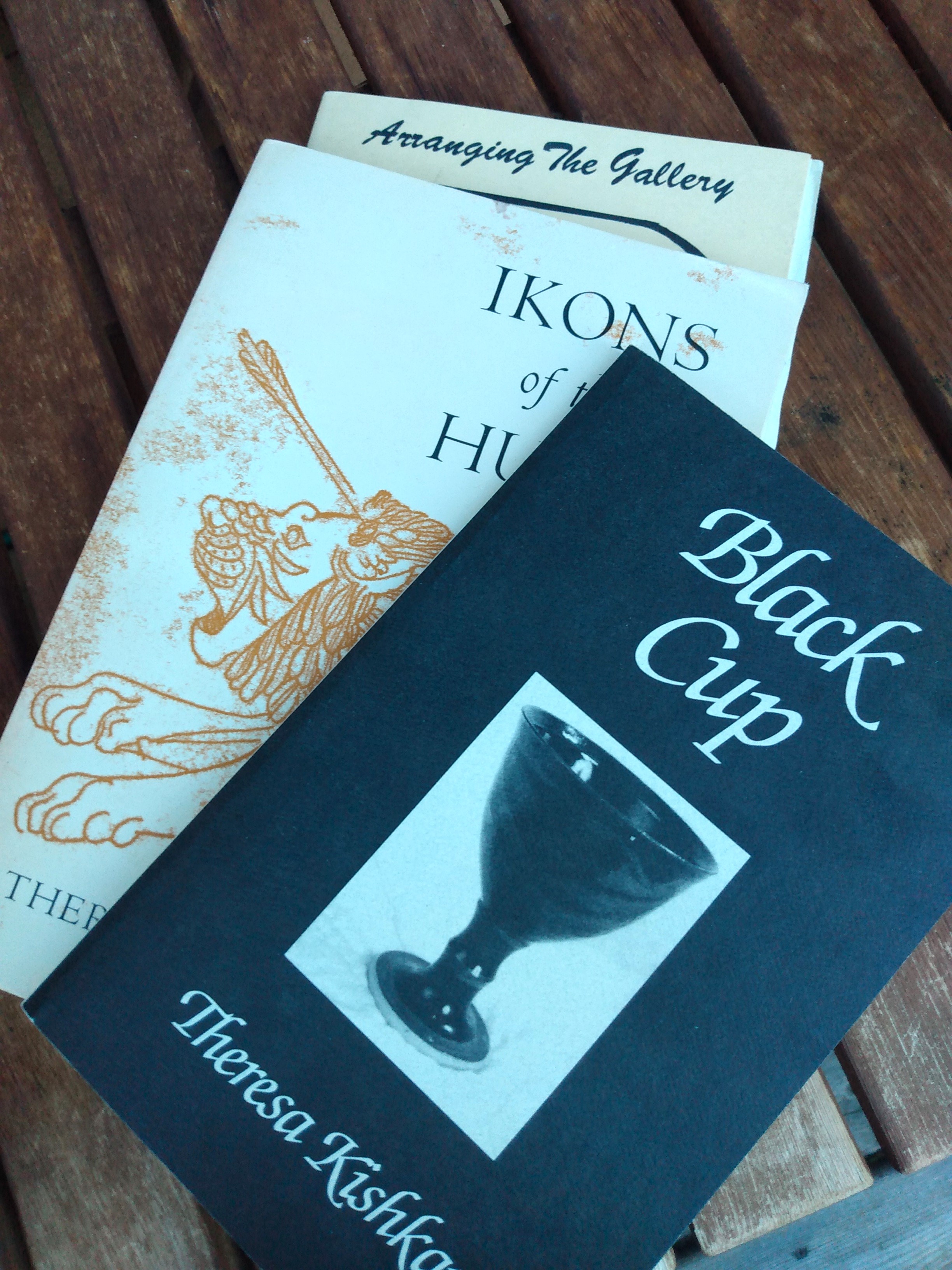

I took some writing courses during my university years. I can’t say that the classes themselves were particularly useful–then, as now, I resisted the idea that sharing my drafts with others was necessary; I felt my writing process was a private one and I’d figure things out for myself–but I did have some good instructors who became mentors and friends. One of them, Charles Lillard, suggested to me that I probably had enough poems for a chapbook and why didn’t I send a manuscript to Fred Cogswell at Fiddlehead Poetry Books. I did, in the spring of 1976, when I was 21 years old, and he wrote back within a couple of weeks to say he liked the poems and would publish the book that same year. There wasn’t a contract. There was no editing. And when Arranging the Gallery came out as Fiddlehead Poetry Book 197, I was mortified by the cover design and I also realized that somehow a whole poem had been muddled in the typesetting (I hadn’t received proofs either!). Fred was apologetic and arranged for a page to be reprinted with a gummed edge and he undertook to send the new pages to those who’d ordered copies. There were a few reviews, mostly positive. On the one hand, it didn’t seem all that difficult to publish a small book. On the other, I didn’t know enough to own the parts of the process I could have been involved with. One of these artless states of being would come to haunt me when I published my second book.

A year later, Robin Skelton, who was the poetry editor at Sono Nis Press after Dick Morriss took it over from J. Michael Yates, asked for a manuscript. I gathered together what I had, including some of the poems from Arranging the Gallery (which had sort of sunk like a stone), and Robin and I organized the sections over glasses of Jameson whiskey in his wonderful study with its tiled fireplace and big chairs. Ikons of the Hunt was the title we agreed on and Sylvia Skelton helped with the copy-editing. I was going away for a year, to Ireland, but I was assured the page proofs could be mailed to me there. Robin had an idea for a cover (after I resisted his suggestion of a nude drawing me of myself), a solarized detail from an Assyrian wall panel. He would write the cover copy.

I remember reading the proofs by daylight and candlelight at the table in the cottage I lived in on a small island off the Connemara coast, returning them, and some months later, in early fall of 1978, receiving a few copies by mail. I sent one to Seamus Heaney, who’d generously given me permission to use some lines of his as an epigram, and I gave one to the fisherman I’d fallen in love with. What he made of it is still a mystery to me.

I returned to Canada from Ireland, intending to stay for only a short period. I’d written prose sketches of my life on the island and a friend invited me to her writing group to read some of them. There were so many questions about the island and what the prose sketches left out that I simply began to fill in the gaps and that became a novella, Inishbream. More on that in a moment. My poetry book was reviewed well, apart from one really terrible one in Books in Canada, written by A.F. Moritz. I remember that I picked up a copy of the magazine at a shop on lower Fort Street and began to read it on my bus ride home. One paragraph in, I was horrified. I wanted to hide. My face was on fire. I imagined every person on the bus could tell my book was pathetic and they were all were looking away, simply to be kind.

Kishkan’s lkons of the Hunt should be

judged by the shameless puffery of the

publisher’s blurb on the cover. She pre-

sents, we are told, “a universe dominated

by age-old dreams and passions.” In the

book we find the stock-in-trade of today’s

most boring and ubiquitous magazine verse:

a flat voice, facile myth-making. a lot of

moons and stones and bones and sea weed

and dream-fish, an easy emphasis on death,

cold, moisture, womb, mot [sic], and silence.

Kishkan supposedly reveals “an ex-

traordinary range of themes and styles.”

The book is depressingly unvaried, with

scarcely ever a change in tone, vocabulary

or any other aspect of style. There may be

several themes, but all are reduced to

monotonous vague keening. a sad-eyed

gaze, and a soft romanticism. What of the

“impressive variety of forms, from short-

lined lyrics to prose poems”? She has

several ways of arranging poems on the

page, but the differences are wholly superficial.

These poems are fundamentally identical in phrasing,

cadence, diction, and mood.

The review got worse (Books in Canada, January, 1979) but thankfully Ikons of the Hunt led my husband John Pass to me. In Victoria for a poetry reading at Open Space, he saw my photograph on the book and suggested to a mutual friend that I be invited to dinner before the reading. The rest is history, our history. Instead of returning to Ireland for good, I went for a short time to tell my fisherman that I wouldn’t be sharing the stone house he was thinking of restoring and John joined me for some travels in Ireland, Wales, England, and Paris. Over our first winter together, I took the sketches I’d written and gave them a structure. I sent the result, Inishbream, to Sono Nis but the feeling there was that I was a poet and this wasn’t poetry so they wouldn’t publish it. I tried many other publishers but no one liked it enough to take it on. In the meantime I was writing poems, slowly, because my ego had taken a bit of a beating, and eventually there were enough for a book. Sono Nis declined that manuscript too but another publisher accepted it immediately with an excited phone call to say he’d had it added to his forthcoming list after clearing the funding with the Canada Council. I never heard from him again. I’d had a baby and when John and I went out to print a birth announcement at the Barbarian Press, making an overnight of it, Crispin Elsted read Inishbream and said he would love to publish it as a private press book, illustrated with wood engravings. It wouldn’t happen just yet because the artist he had in mind for the engravings was busy but if I could be patient, he promised a beautiful treatment for my story.

I was patient for 18 years. Reader, I cannot say I always believed that Inishbream would finally see the light of day. In fact John says that the novella lurked in our house like a dark sister and I know he’s right. I had another baby and then another and somehow I lost most of my confidence in my work as a writer. That third collection of poems shape-shifted as I slowly added to it, poems about motherhood, about regret, about love. It became Black Cup and eventually Robin Skelton, now editing for Beach Holme Press, accepted it. I asked that we request cover matter from other writers, and I chose the image for the cover, though the photographer who took the shot somehow lost his focus. Remembering A.F. Moritz’s observation that, “A few years ago the world’s Kishkans were regaling us with ‘nacreous’, ‘alabaster’, and ‘diaphane’ “, I rigorously avoided such terms! In those years, I was still typing my manuscripts from handwritten drafts and I kept thinking of Inishbream, typed on yellow paper, and some nights it felt hopeless. Maybe those were the nights I had no sleep because of sick children but I recall my yearning for not only the world that inspired the novella but also a writing world that somehow included me. To be sure, there were good things that came out of the blue: a composer writing to ask for permission to set some of my poems to music, a composition that received its premiere at the Scotia Festival in 1987, sung beautifully by Rosemarie Landry. Letters from readers. A few wonderful invitations.

But I no longer had access to the lively spirit that allowed me to write poetry. There is no way to explain this but I knew it was gone. Then one summer, on a family camping trip to the Nicola Valley, I was filled with such urgency to write down every detail, to describe every moment, and to record the names and dates of those buried in the little corral of graves beside the Murray Church. This became a lyric essay, “Morning Glory”, and the experience of writing it was new and rich. I wanted to continue exploring the possibilities of the form and found myself writing constantly. The essays became Red Laredo Boots and after many rejections elsewhere, New Star Books took the manuscript, or more specifically, Terry Glavin found a place for it in his Transmontanus series.

At the very end of the 1990s, proof pages began to arrive by fax from the Barbarian Press, with the fervent hope that I could attend to them immediately as the press was inked* and ready. I’d seen some of the drawings for the engravings because the artist, John DePol, wrote to ask me about certain details. His was a clear and beautiful style, moody skies, a scene in a bar that reminded me of Jack B. Yeats. Over the 18 years that passed between Crispin reading the original Inishbream manuscript and its publication, I’d made a few changes, most of them as I transferred the text from paper to word processor, taking Jack Hodgins’s advice to think of revision as “re-visioning”. He recommended opening a new file and starting afresh, using the old manuscript as a template. I’d typed and changed, only a little, and sometimes Crispin would phone to make a case for the yellow manuscript version. And he was always right. The original was somehow true to the young woman who wrote the sketches in a notebook on a rocky island off Ireland’s west coast. I went to the Barbarian Press for a weekend to watch the binding of the Deluxe edition—the book was published in 3 states, the first quarter-bound with green Japanese silk, with covers created by John DePol; the second quarter-bound in dark green leather, with a folio of 10 proofs of wood engravings, a slipcover holding both; and a Design edition, bound by Hélène Francoeur in goat and fish leathers, housed in clamshell box with driftwood and brass elements, and including a folio of all 21 engravings. It’s an astonishingly beautiful book in these treatments and I have to say every hour of those 18 years was worth the wait.

By the end of the decade, I’d written a handful of new essays, I’d published several chapbooks, one of which, Morning Glory, won the bpNichol Chapbook Award, but what truly absorbed my time and imagination was a novel, begun – as was Inishbream— as a poem, a long poem about horses, occasioned by an autumn encounter with a small herd on the Pennask Lake Road. But I began to develop another strand of narrative, one wholly fictional, and it was as though I was living two lives, one set in 1906 and one in the current moment. If it had been difficult to find a publisher for my 3rd poetry collection and for Red Laredo Boots, I was about to learn about true rejection and a certain resilient patience.

*just to clarify that the book was handset and printed letterpress, one page spread at a time, so time was of the essence. You can read a bit more about this here: http://barbarianpress.com/archives/inishbream.html

To be continued…