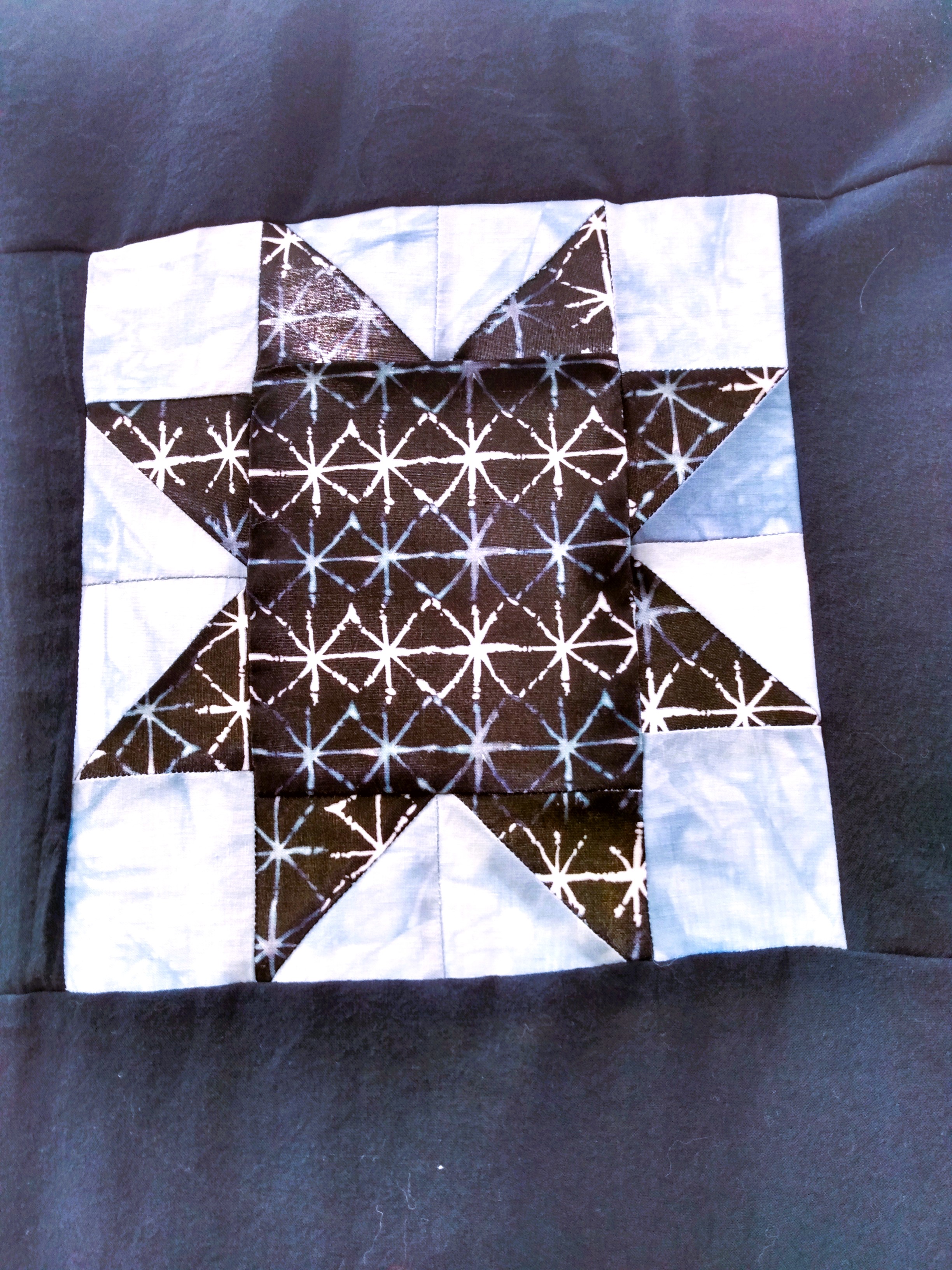

This is a passage from a long essay (still unpublished), “On Swimming and the Origins of String”. Today I am hoping to complete a quilt top, simple stars pieced of Japanese print and scraps of woad-dyed cotton, sashed with a deep blue cotton-linen blend. For the actual quilting, I want to try something to give the piece more texture and so I’ve been remembering particular encounters with beautiful work by women that speaks to the quality of living fibre, living structures at the heart of artistic creation.

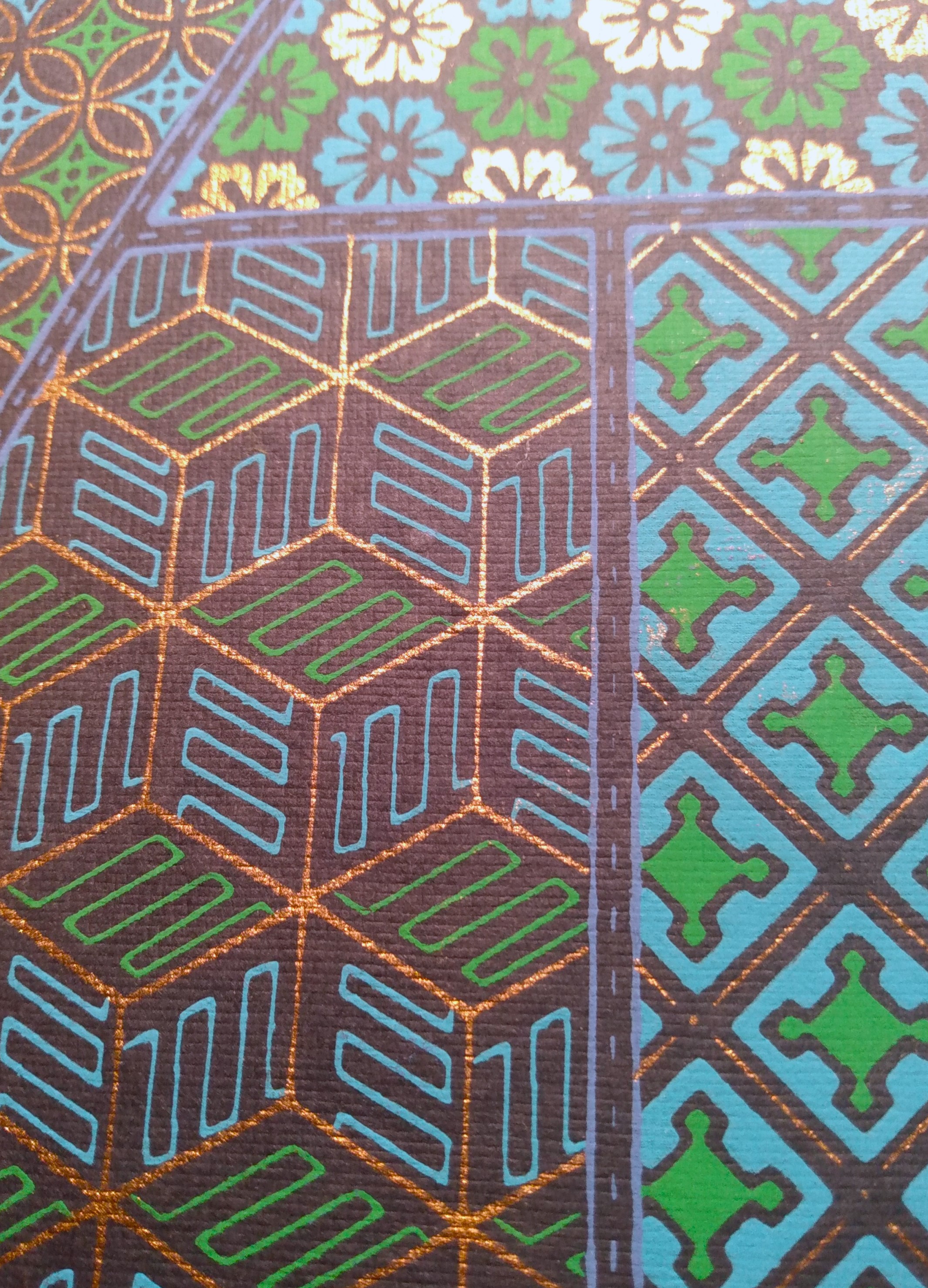

In Baja last year, I entered a small gallery in Todos Santos and was drawn to a huge painting. It was mostly blue, many shades, the same blues I saw most days of my time there, vivid aqua, ultramarine, saturated cobalt, Egyptian blue. And fastened to the work, painted into it with impasto or maybe some sort of glue, was a fragment of fishing net. I stood in front of the work and brushed tears from my eyes. I had been swimming every day in Baja, first thing in the morning in a blue pool shaped like the symbol for infinity, and later in the day in the ocean, the wild Pacific and then the calmer waters of the Gulf of California at El Tecolote. I had been taken into the blue water, under the blue sky, and I felt cradled in it, a hammock of coarse rope, rocked by currents. The painting spoke of that relationship, the layered blue, scrap of net. I couldn’t get it out of my mind. It looked like it was made of hemp rope, not the high-density polypropylene or polyethylene or nylon most fishing nets are made with now, giving them the capacity to go on forever in our oceans, abandoned or lost, marine creatures entangled in their filaments.

In some ways I was reminded of Polish textile artist Magdalena Abakanowicz’s magnificent sculptural works, the ones known as Abakans. I haven’t seen them in person but have followed the reviews of the exhibition at the Tate in London: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope. In an ideal world, if I could travel at will, at the drop of the hat knit by Cowichan women and hanging on a hook by my front door, I’d have spent hours looking at these brilliant three-dimensional works, suspended in air, turning a little in drafts. They are like hollow trees, vulvas, caves, encompassing cloaks, wombs, embellished with lichens, entrails, long intricate veins or roots. One dark one, bifurcated, reminds me of my lungs seen in an xray image: the cilia, the primary bronchus, densely and richly textured. Deep charcoal, olive, red, saffron, woven of sisal, fleece, horsehair, flax, haunting in their, well, I can only say otherness. But it’s an otherness that we know and long for. Seeing them on film, I want to touch them, trace my fingers along their openings, enter their openings to leave the world behind. She knew fibre, was drawn to its possibilities and potentials “I see fibre as the basic element constructing the organic world on our planet… It is from fibre that all living organisms are built, the tissue of plants, leaves and ourselves… our nerves, our genetic code, the canals of our veins, our muscles… We are fibrous structures.”

Seeing the painting and thinking about the Abakans, I find myself wondering about how to make a partial turn from the quilting I love so well to constructing something organic and emblematic of the ideas I have constantly: the cradle of the earth, the lines connecting us to the living world, the temporary and permanent nests we yearn for and abandon. I think of gathering rope to add to the stash I’ve picked up on beaches, roadsides, and then somehow knitting it into huge bags to hold, well, what? Something, if only possibility. I think of those ropes at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis, coiled in readiness, and I imagine the scent of them, ripe and redolent with that possibility.

Sometimes, when I’m swimming in the lake, a cirrus cloud formation will float over and I wish for it to settle on me like a net. Or I could turn over and lie in, a hammock of sky, a bag cast out of the heavens.

Draw history through the eye of the longest needle in your basket, the twined thread—flax stem, inner bark of a pine, pounded nettle, strands of a coarse-haired sheep—and make the seam to hold the bag together. In it, the story of the blood clot, the blue lane of the pool, the tiny merganser chicks light as the air itself. This is yours, to give away or to keep.

A little later, that same day: