Yesterday I was working on this quilt, two lengths of hand-dyed linen sandwiched with organic cotton batting. I know I keep writing about this but every day I find out something new. Or old. Maybe I just wasn’t paying enough attention. But in-between stitching, I’m studying several books about Paleolithic cave art — the text-heavy theoretical ones and the more visual ones. Through the wonders of interlibrary loan (thank you, Sechelt Library!), I have Cave Art, a magnificent guided tour of rock art sites, by Jean Clottes. He tells us in his introduction that he has tried to create an imaginary museum and if you’ve read my essay “Museum of the Multitude Village”, in Blue Portugal and Other Essays, you will know that I am already in line, ready for the tour.

So I sit with the book on my lap, studying the wonderful plates. There are some images I remember. This horse, for example, called the Chinese horse, maybe for its resemblance to Przewalski’s horse, the Central Asian animal that was almost extinct and has been brought back from the brink. They share similarities in conformation and colour.

I took this photograph at Lascaux IV, the astonishing centre of parietal art in the shadow of Lascaux cave. (The cave itself is off-limits to anyone other than a handful of researchers but the replica is really glorious.) I love this horse. In fact I love every horse I saw, at Lascaux, at Rouffignac, at Font de Gaume. But what also caught my attention here is the line below the horse — a free-drawn exuberant trail across the cave wall. Is the horse following a trail? Does the artist want us to know something about him or herself? Is it an inventory? Will anyone ever know for sure?

When I sew, I follow a line. My needle finds it in the fabric. It meanders, it spirals, it stretches out like a road on a map, like a river in a landscape. When I see some of the brush work in these paintings, I feel a kinship, across thousands of years. It is a wonderful thing to make a mark, to leave a trace — of thinking, of ceremony, of an encounter with mystery.

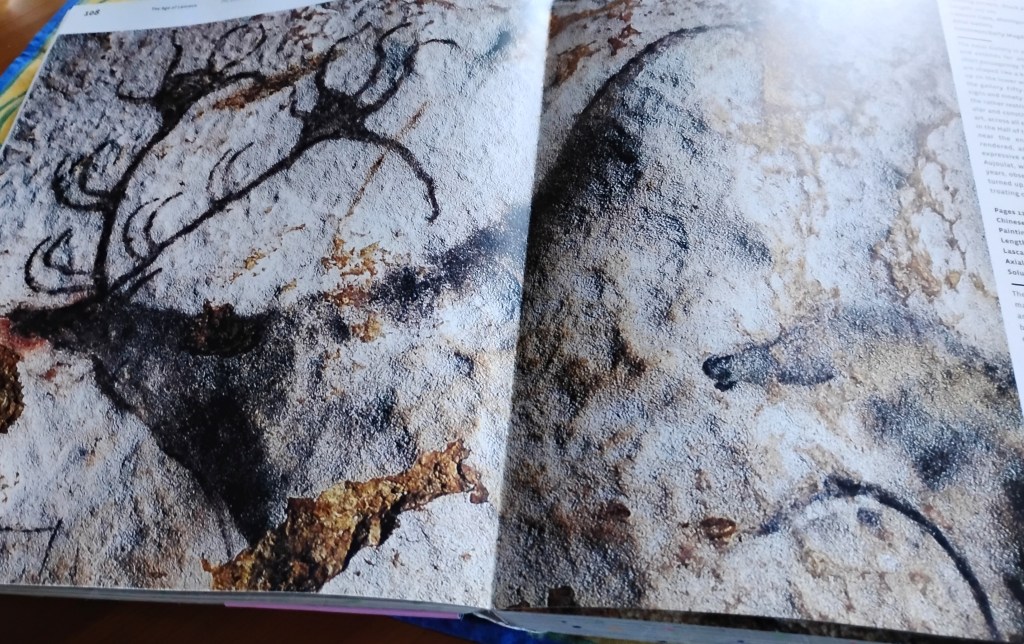

One of the plates in Cave Art is this black stag, also at Lascaux.

The paintings at Lascaux date to something like 17,000 years ago, possibly as old as 22,000 years. The artists made use of a full polychrome palette: deep blacks, warm browns, reds, yellows, even a kind of mauve. What I love about this stag is the wildly original depiction of its antlers. Imagine the artist, tilting the stag’s head upward, as though bellowing, then–I am imagining the body first, then the antlers–following the line up and up to create those antlers. With joy, I am certain.

I think of Barrie Cooke and his Megaceros hibernicus (also called Megaloceros giganteus, the Giant Irish elk, though it’s not actually an elk, nor Irish), showcasing in a not dissimilar way, the otherworldly antlers. I think of him and these animals every time I see a bull elk in autumn, ready to gather and defend his harem. I’ve heard the elk bellowing in the woods, two at the same time, challenging one another.

So I read, I study the images, and I run my needle through the stretched linen, a skyscape, a waterscape, dyed with indigo on a late summer morning. A quilt is growing under my hands. What will it remember of the weight of the book on my lap, the distance my imagination is travelling, the distance between blue stitches, hoping a horse will find the trail.