A few weeks ago, at the Friends of the Sechelt Library book sale, I found a copy of M.F.K. Fisher’s Two Towns in Provence. It is exactly the right book for the weather we’ve had this summer (after 13 weeks without rain last summer, I said I’d never complain about rain again; so this is me, not complaining about rain…). I love her books anyway and this was one I hadn’t read. So it went onto my bedside table and once I’d finished Belinda McKeon’s extraordinary novel, Tender, I began to dream my way back to Aix-en-Provence.

We spent four nights there a few years ago. We’d been in Paris and were meandering to Venice, where we planned to spend a week and ended up asking the host of the small hotel we’d fallen in love with if we could book another week — we couldn’t bear the thought of leaving, not once we’d found our favourite grey canals and a little bar where a glass of Prosecco cost a euro and if you asked for another, the bartender simply brought a hose to your glass because of of course the Prosecco was on tap.

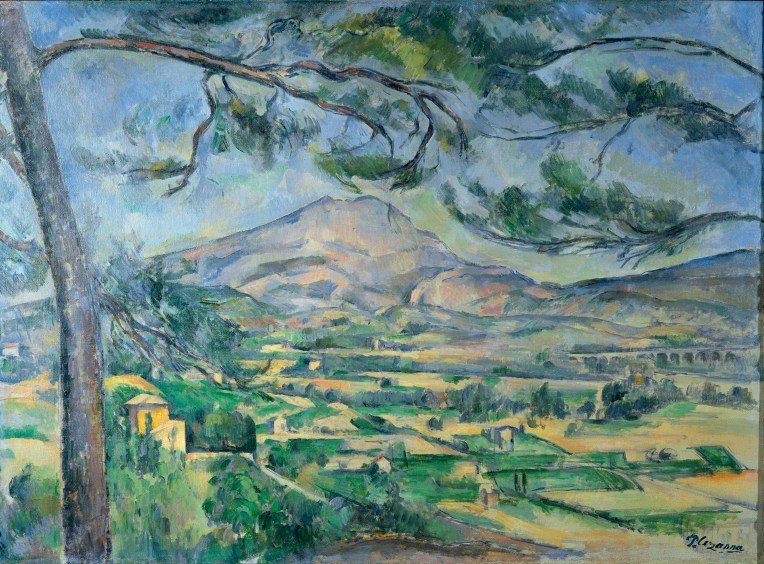

Stepping off the train in Aix was like walking into a Cezanne painting. The light, the pines, the view of Mont-Sainte-Victoire…Even the smell, if that doesn’t sound too weird. Old tile and water, plane trees and their leaves underfoot — it was November. It was a bit of a walk to our hotel and John was hungry. So he insisted on stopping at a corner store, a 8 à Huit, and coming out with a huge sausage and a bottle of red wine. He was gleeful at how little he’d paid, pleased that in France one could go to the equivalent of a 7-11 and buy something decent. (I didn’t say a word. The sausage looked suspiciously fatty and industrial.) And once we found our hotel, with its bright yellow curtains and blue shutters, he sat on the bed and opened the wine. How did he slice the sausage? I don’t remember but this was post-9/11 so I’m sure he didn’t have his Swiss Army knife. No matter. The sausage was terrible. The wine was pretty rough. But we found one of the gorgeous markets later that day and bought beautiful bread, cheese, olives, and other provisions for picnics. And we found an amazing park nearby, with a small museum in the former home of the great French poet Frédéric Mistral who was also a lexicographer of the Occitan language. There were wonderful pines there and benches to sit in the sunlight–« Les arbres aux racines profondes sont ceux qui montent haut. » ;“Trees with deep roots grow tall.” — and for one of us at least, the chance to gnaw at a little more of the 8 à Huit sausage.

And M.F.K. Fisher’s book is drenched in that sunlight, the sound of water, the narrow streets between ancient buildings.

It is the same about the whole sound of the place. Jean Cocteau has said that a blind man in Aix would think the city wept; but that is not my hearing of it. Instead, the music of the fountains lies under and in a mysterious way over every other, with a melodious gracious mirthfulness…on my own map, that is. And then I hear, always, the street sweeper of the Rue Cardinale, who in the dark of the night turned on the water from the little fountain of St. Jean de Malte and let it flood down the gutters, and then swept them with a broom made of long twigs which scratched forever into the unconscious listener in me. In full moon and dark, in the silent street, this sound became familiar, always almost frightening, always a strange reassurance of order and courage in the face of complete silent loneliness.

The light and dark of a secret map would of course be the most impossible to print. Even more than there is no ink for the smell of the Saturday Market or the sound of a broom in the dark gutter, there is none for some of the colours I shall always see clearly in my own cartography.

I remember Aix and on my own map, there are two travellers on a bench under pines, there are two lovers walking to the Cours Mirabeau to find a cafe for dinner, the fountains and their music part of the map’s legend, there is a golden light and churches, the prospect of Venice, and the creak of blue shutters in the wind that gave the poet his name.