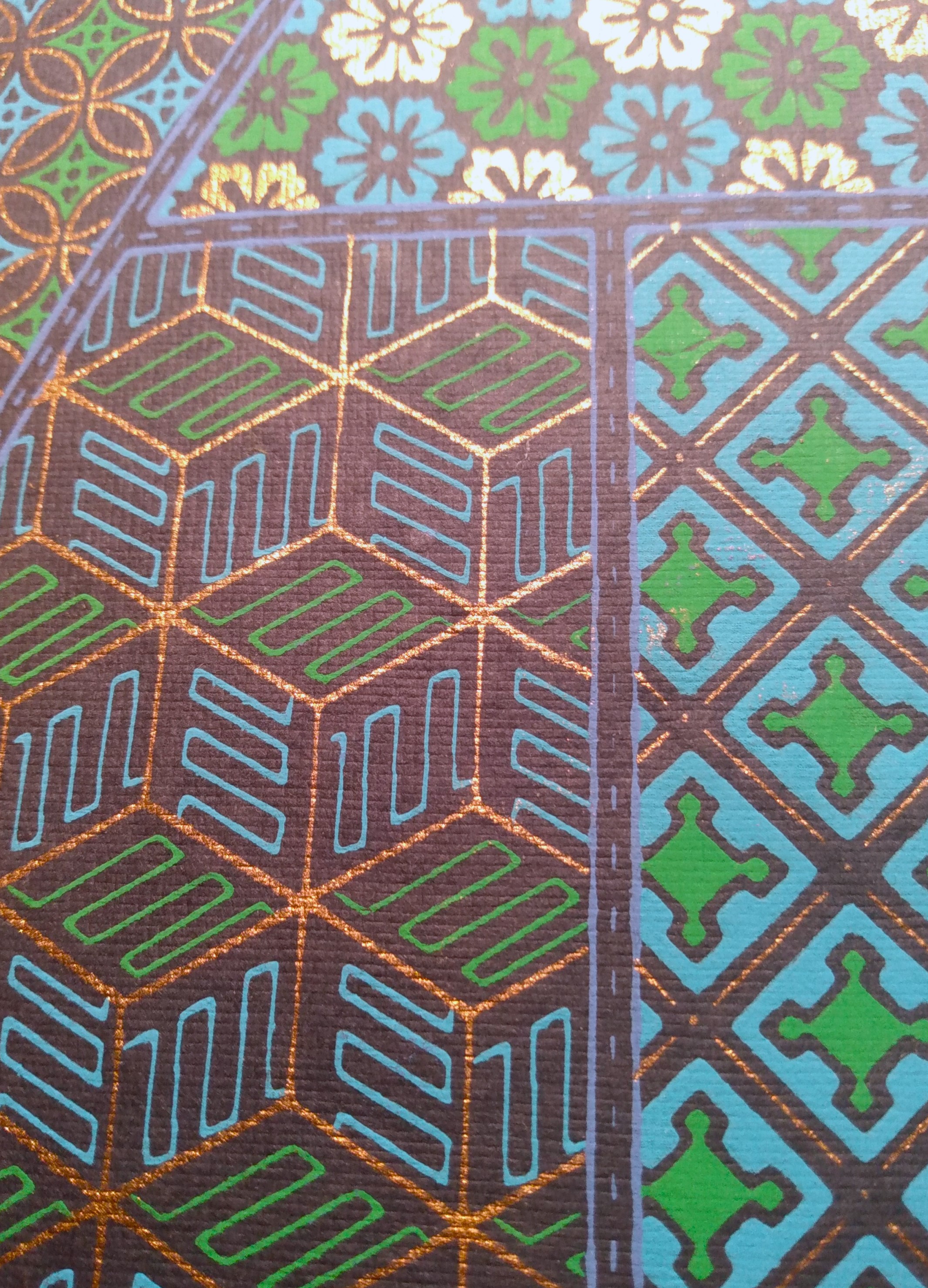

I don’t really keep a regular journal. I’d like to be that person, and maybe I once was, or at least I was when I lived in Ireland, when I travelled in Europe as a young woman with a backpack and a little notebook tucked into one side pouch. On trains, I’d be noting every detail. In Ireland, it was as though I had my finger on my own pulse on a daily basis. Reading those old journals is interesting to me but in some ways it’s also excruciating to realize how self-absorbed I was, perhaps out of necessity. I was my own company for the most part because I travelled alone, lived alone. A few years ago I bought the little book in the photograph at a Christmas craft market in Madeira Park. It was handmade by a woman in Roberts Creek. The cover is yellow cedar, edged with black walnut. The binding is Coptic stitched, sewn with waxed Irish linen thread, each signature quarter-wrapped with screen-printed Indian cotton paper.

I

I wanted to write in it regularly and I wanted what I wrote to be worthy of its beauty, the time and care its maker took to create it. And I do try to write in it from time to time but reading back, I see that I’ve been trying to work out my relationship to writing and publishing and it makes me kind of sad to recognize how unresolved those things are for me. Partly this is because the work I’ve been doing is personal and I wonder how it would be of use or interest to anyone else. And partly it’s because I’m no longer young and the writing world feels to be like a place for young writers, their concerns and their values. Reading back, I see that I’ve been pondering this for at least 2 years, without any clear notion of what to do about it. Maybe there isn’t the kind of clarity I’m hoping for.

At night lately, when I’ve been awake, I’ve been re-reading the artist Anne Truitt’s 3 books, bought many years ago, read with great interest, and still of great interest to me. Daybook, Turn, and Prospect, each of them subtitled “The Journal of an Artist.” I first discovered Daybook about 30 years ago, a young(er) woman returning to writing after the intense early years of motherhood. Her quiet and elegant entries about her life, her work, well, they spoke to me with such depth and warmth. I remember looking for images of her sculpture and not really understanding it. But when I learned there were other books, later on, I bought them and found in them that same quiet exactitude. I still don’t entirely understand her sculpture but I see more and more resonance in it and I respect the artist. She writes, in Prospect, that after she’d figured out how to put the wood together for her columns, and how to mix the paints to the right consistence so that she could layer the works with repeated coats so that the radiance of the paint itself was released, “the sculptures had become what I have been making ever since: proportions of structural form counterpointed by proportions of metaphorical color–essentially paintings in three dimensions.”

Truitt is one of 3 artists I’ve become interested in over the years. Ann Hamilton and Magdalena Abakanowicz are the other two. I am drawn to the materiality of their work, the complexity of it as it moves easily between (and over) methods and outcomes. I look at Abakanowicz’s magnificent Abakans textiles and realize how one-dimensional my own work is. Ann Hamilton’s indigo work, so multi-layered and rich. I wonder if it’s too late to somehow draw the threads of my thinking and doing together in some organic way that I haven’t yet found. Maybe too late but maybe not? To that end, I’ve been trying to figure out how to knit netting because somehow that feels like the right direction to take.

I’ve just learned that there’s a 4th Truitt book, edited by her daughter (Anne Truitt died in 2004), Yield, and I can’t wait to read it, can’t wait to have her company in the dark hours when every regret, every blank journal page or self-absorbed notebook, accumulates in the heart and mind to remind me of what I haven’t accomplished in my life, either through neglect or too little confidence or even a lack of courage.