Some mornings I open Virginia Woolf’s A Writer’s Diary to see if there’s something I could take as advice or consolation or even a divination.

divination(n.)

late 14c., divinacioun, “act of foretelling by supernatural or magical means the future, or discovering what is hidden or obscure,” from Old French divination (13c.), from Latin divinationem (nominative divinatio) “the power of foreseeing, prediction,” noun of action from past-participle stem of divinare, literally “to be inspired by a god,” from divinus “of a god,” from divus “a god,” related to deus “god, deity” (from PIE root *dyeu- “to shine,” in derivatives “sky, heaven, god”). Related: Divinatory.

What is hidden or obscure. Maybe that’s what I’m looking for, hoping for, rather than inspiration from a god. (What would that look like, I wonder?) So much is hidden. What happens next, to me, to all of us. Is there advice I could follow to accept with grace the years ahead? There are perils in being human, in being alive, anticipating the future. Maybe my writing is a way to modify my own anxiety, to offer an alternative: well, the world is on fire but I can work on a novella in homage to Mrs. Dalloway, with a party situated outside under honeysuckle with music played on cello and oud, or a novel set in a small fishing village at the end of the road where women stitch in the community hall and a secret room opens to reveal paintings of trees.

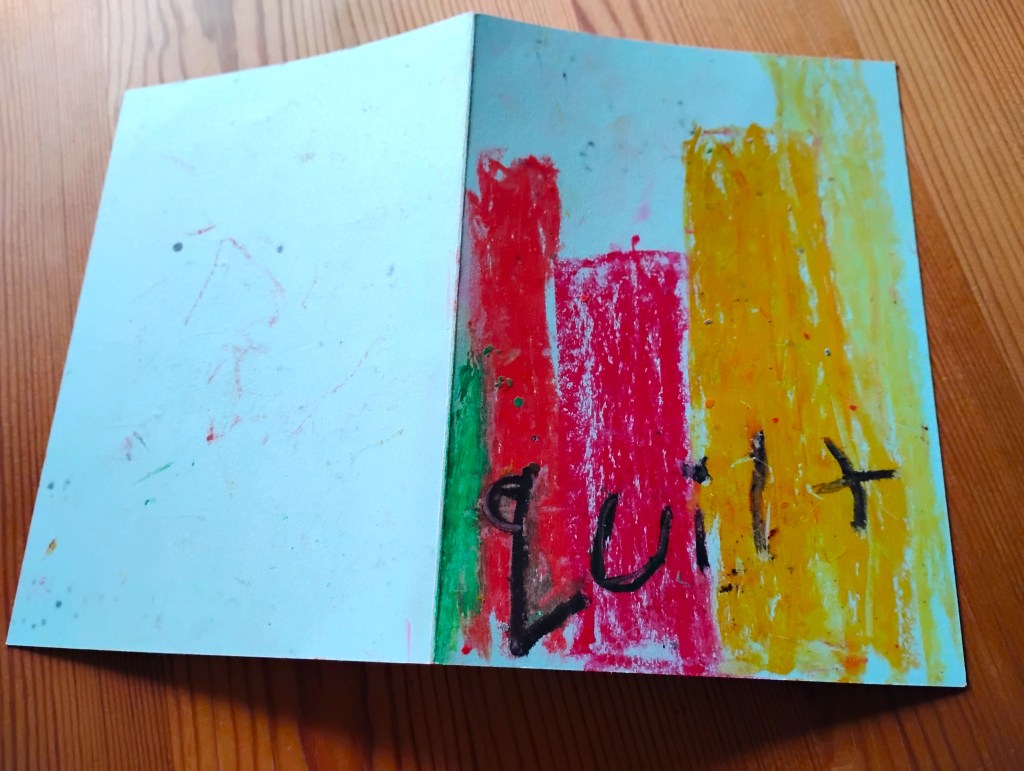

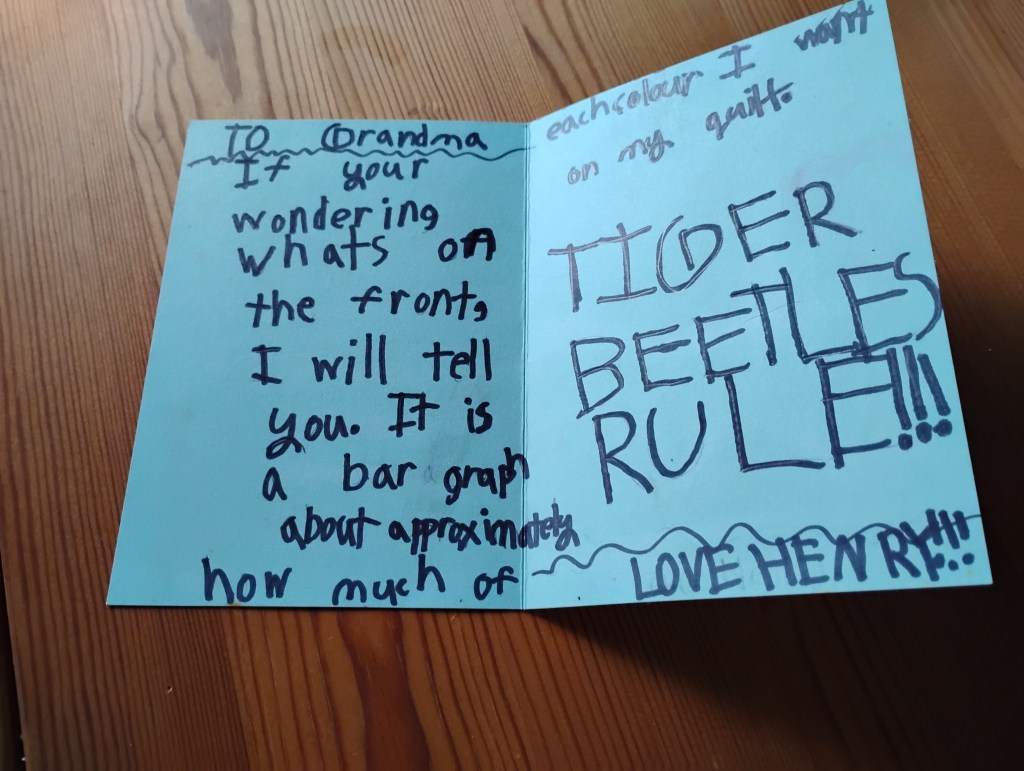

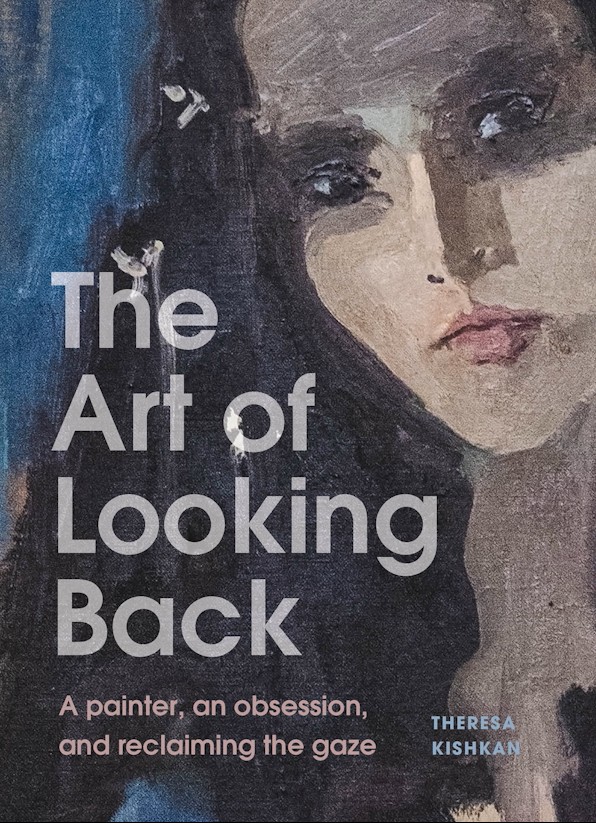

I wrote about the Diary and Mrs Dalloway here and re-reading this post I realize that I was perhaps edging towards my forthcoming book; the bookseller I mention and his shop and those years are at the heart of The Art of Looking Back: A painter, an obsession, and reclaiming the gaze. (The bookseller even has a tiny cameo though I bet you won’t be able to find it! Maybe I’ll offer a prize if you do.) When I read the passage I found today, written on February 2, 1931, Virigina Woolf is about to finish writing The Waves, possibly my favourite of her books. I first read it as a young woman, well, a girl, of 18. I don’t think I quite understood it then though I could lose myself in the rhythms of the sentences, the dialogue, the beautiful passages in which I recognized something of my own sensibility, which wasn’t usually the case when that 18 year old read a novel:

There is, then, a world immune from change. But I am not composed enough, standing on tiptoe on the verge of fire, still scorched by the hot breath, afraid of the door opening and the leap of the tiger, to make even one sentence. What I say is perpetually contradicted. Each time the door opens I am interrupted. I am not yet twenty-one. I am to be broken. I am to be derided all my life. I am to be cast up and down among these men and women, with their twitching faces, with their lying tongues, like a cork on a rough sea. Like a ribbon of weed I am flung far every time the door opens. I am the foam that sweeps and fills the uttermost rims of the rocks with whiteness; I am also a girl, here in this room.

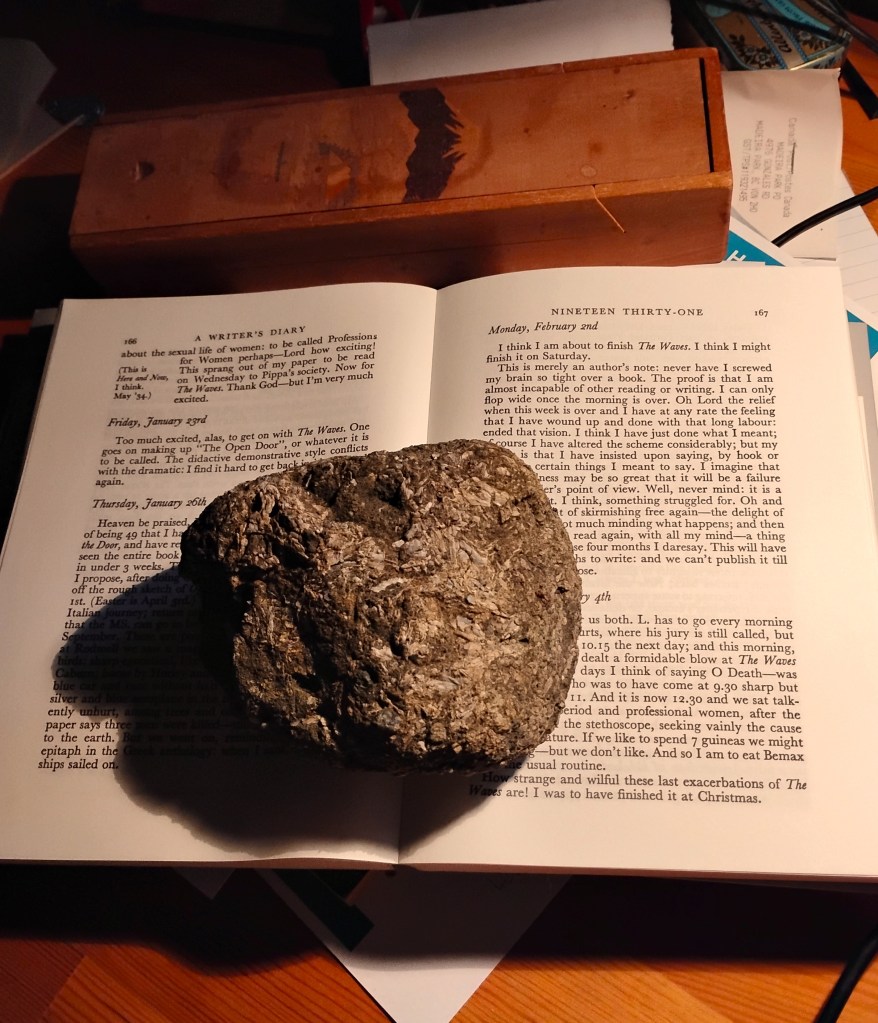

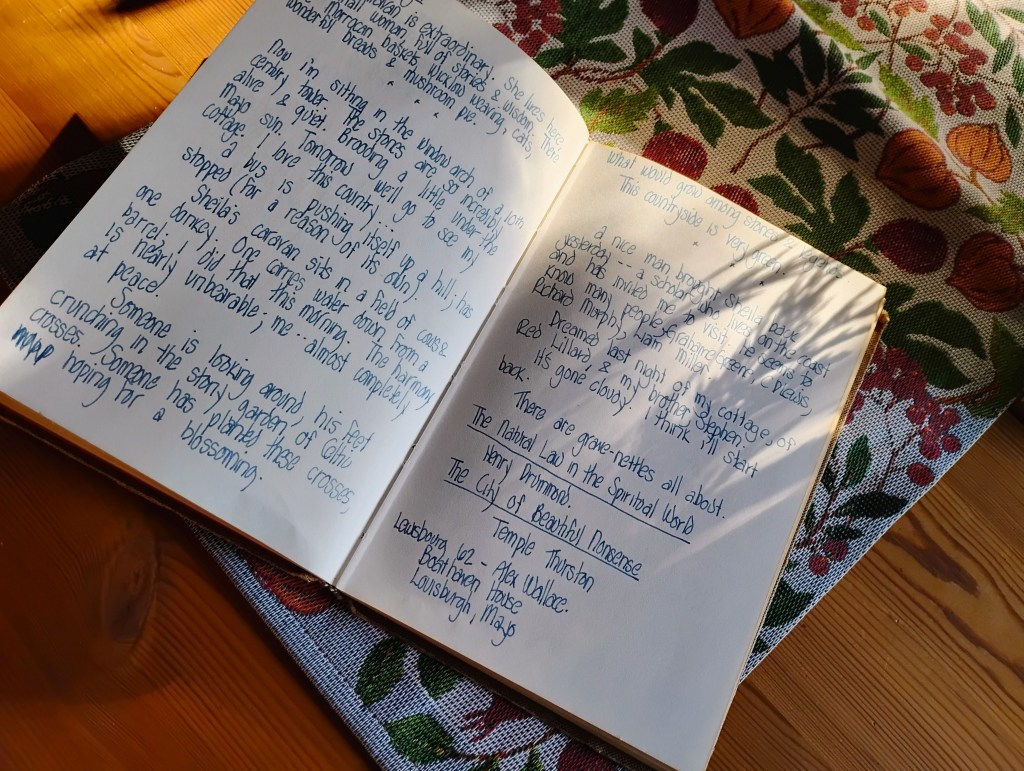

At my desk, the Diary held open by a piece of Oligocene sandstone filled with tiny shell fossils, I feel porous enough to let those sentences enter my thinking. She looks forward to a brief time of freedom, of being idle, the book written, not quite ready to be published (it would come out in October of that year, published by her own Hogarth Press).

…my feeling is that I have insisted upon saying, by hook or by crook, certain things I meant to say. I imagine that the hookedness may be so great that it will be a failure from a reader’s point of view.

Never a failure from this reader’s point of view, not as an 18 year old, nor as a woman in her 70s. What happens next. “Like a ribbon of weed I am flung far every time the door opens.” I feel porous enough to let the sentences do whatever they want.