There are gods here, too. (Herakleitos, 74.)

The way you feel after a swim in water that is full of weather somehow, lit green by sun and reflected cedars, pierced with dragonflies, shadowed by the mountain we live under, and wrinkled by light air movement this morning. You are never more yourself, but you don’t even begin to think that while you are there, your own reflection in the surface. You turn and turn in the water. If you are quiet enough, the mother merganser will pass very near with her newly-hatched ducklings, 17 of them, tiny and buoyant as a wish.

–from an essay, “On Swimming and the Origins of String, with a Bow to Herakleitos”, published in the Temz Review, Issue 30

posts

redux: bluets, or the radiant days

Note: this was written five years ago. This family is visiting us and yesterday we swam in Ruby Lake, returning home for coffee on the upper deck with dragonflies darted overheard and perched on the stakes holding the lilies aloft. (Anyone interested in Red Laredo Boots–the book, not the boots themselves– can contact me. $5 a copy, plus postage…)

_________________________

A little more than a week ago, we spent time with part of our family in country we’ve loved forever. We stayed at Lac Le Jeune and we ventured out each day to swim in Nicola Lake (where we camped when our children were young, every summer, and where I began to realize that strands of landscape, history, and the scales of pine cones could be bound together as essays, the ones I first wrote in Red Laredo Boots and the ones I am still writing) or to explore the old part of Kamloops and swim (briefly) in the Thompson River. We would have done yet another familiar thing—lunch at the Quilchena Hotel, then a poke through the old store there, where I did finally buy the boots longed for in the title essay of Red Laredo Boots after receiving exactly the amount they cost in payment for another essay in the collection—but the hotel is closed because of the pandemic.

At Nicola Lake, I was swimming along the ropes delineating the safe area, when I noticed that every cork bobber had damselflies on it. Sometimes two, or more. They were so delicate and beautiful, the blue of them not quite the colour of the sky and certainly not the tea-colour of the lake, but an ethereal aqua. I went back to shore and told John. So he swam out to see them too. At times like that, I realize how little I know about bugs in general and damselflies in particular. The field-guide I had with me told me that these were almost certainly American bluets. That this genus, Enallagma, contains most of the damselflies in our area. that identification of the seven species we’re most likely to see isn’t easy for someone like me, a non-specialist, and that the mating damselflies remain connected until the female oviposits on the stems of the rushes and the resulting offspring hang around the submerged plant matter for the small invertebrates swimming near.

Do I need to know the species? No. The names of the possibilities are like a summer poem: Northern Bluet, Tule Bluet, Boreal Bluet, Familiar Bluet, Alkali Bluet, Marsh Bluet, Hagen’s Bluet. Knowing this, and that they’ve been around for 250 million years, and that they graced the cork bobbers while I swam, looking back at my own beautiful family on the shore, was enough. And while we swam and looked at bluets, an archaeological team was walking the sand, in search of remnants of tool production, was measuring the remains of kikuli depressions in the grass between the change rooms and the beach, and an eagle kept passing over the area, back and forth, flying so low I could see its empty beak. A boy stretched out in grass at a marmot hole and the air was dry and fragrant with pine sap. For a moment I couldn’t tell if the boy in the water with the boogie board was my grandson or his father, 35 years ago, if the girl stretched out on a towel was my granddaughter or her aunty, also blond and eager to swim, whether the young woman alone under the pine was the mother of my grandchildren or myself, longing for a quiet moment to think and remember. Boreal Blue, Familiar Bluet, stitching the years together.

“a breeze makes its own music of capiz shells hanging over a table”

It’s been cooler. Still sunny, mostly, but sometimes a breeze, and overnight the temperature falls a little so that when I go down for my swim, the water is warmer than the air. Yesterday a merganser surprised me by jumping onto a log near one end of the beach. Another was fishing just beside her. Was it one of this year’s babies, almost grown?

Last week was busy and this week will be busier. Our Edmonton family arrives tomorrow. And I am working to finish the copyedits for my forthcoming book, The Art of Looking Back: a painter, an obsession, and reclaiming the gaze. It’s interesting to me to spend time looking at the writing at the level of commas, citations, paragraphs. Every now and then, the copyeditor comments on elements of the narrative, not to suggest changes or anything, but to say, Wow, that must have been a shock, as she responded to an extract from a letter in which the painter was essentially telling me he would make naked images of me available to everyone. And yes, I think (all of over again), it was a shock. And I’d put it away.

A photographer came last week to spend a few hours taking photographs of some of the images referenced in the book and also some potential author photographs. She was just wonderful: Chelsea Roisum. We talked, laughed, talked some more, ate the lunch John prepared for us under our vines, and on Friday she sent me a file of her images. She hoped there would be a portrait I was happy with and oh yes, there were many. But maybe this one most of all, because it echoes two sections of the book, one about the Karyatids in Athens, supporting the entablature of the Erechtheion, and another in which I hold up the beam (the one above me in the photo) while John nails it into place.

Summer goes on. The world is a terrifying place right now. But here, on this piece of land I’ve known since February, 1980, a breeze makes its own music of capiz shells hanging over a table, and I am lost in recollection.

Note: Chelsea generously said I could use some of the photos.

Consider the lilies

“Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin.” (Matthew 6:28)

Consider the lilies by the front door. They do not spin, not yet, as they’ve opened on a still morning, without a breeze. But they’ve reached the wind-chimes, the eaves.

Consider the loons, the ones we saw this morning flying over the lake as I swam and John sat nearby, reading. I’ve never seen more than 2 or 3 loons at a time but there were at least 10, one of them calling, calling, that unearthly tremolo, and 4 returned to the water, past the little islands. Later, a single one flew to the bay near where I was swimming, alone.

Consider the coyote pup, the one we’ve seen lately just to the south of our house, not this one (who came a dozen years ago, or more, in much the same routine) on the mossy area we call a lawn. Last weekend, several evenings this week, and then this morning, before 6, as I worked at my desk, it appeared just below my window where 4 stairs lead up to a little porch below my study. Consider its beautiful face, its open ears, and the unexpected sight of it nibbling salal berries at the edge of the woods.

Consider the nuthatch exploring an empty birdhouse, a huge summer spider in the sink this morning, a hare beyond the garden last evening, the young buck I heard John talking to from the upper deck, with its new antlers, the western tanager chasing a Steller’s jay away from the post where I’d put pumpkin seeds, consider the barred owl calling last night, and the night before, consider the trout jumping as I swam the other day, right out of the water, and consider the quiet as the moon set yesterday morning.

redux: watching the young queen

Note: 4 years ago it was hot and I was watching bees in the oregano. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

—————————

This is the summer when I realize how much I don’t know. Don’t know about boat engines, don’t know about bees. I’m trying to learn about both. The boat engines I’ll save for another day. But the bees? One species at a time, slow and steady.

Every morning I sit here with my coffee.

And every morning the oregano is lively with Bombus species, sometimes 4 or 5 quite distinct ones. If I pay attention, I see that there are slightly different behaviours at play. There are bees who will tolerate another coming to the blossoms they are at work on. A single head of flowering oregano might host 3 bees at a time.

But yesterday morning I saw a species I’d never seen before. It was very black, with a yellow head resembling the Corinthian helmets worn by hoplites, or citizen-soldiers, in ancient Greece. It had a single thin ring of yellow right at the end of its posterior. I posted a quick (and blurry) photograph on Twitter, tagging a woman who knows about bees, and learned it was Bombus vosnesenskii, the yellow-faced bumblebee.

One of the bees was nearly twice the size of the other and it was almost certainly a young queen. She tolerated no other bees on her blossoms, not even the smaller one of her own species. I watched her forage, hoping she would discover the new umbels of tomato flowers, replacing the ones that burned off during the terrible heat of two weeks ago. This species is an important pollinator of greenhouse tomatoes apparently. I watched but the oregano was too luscious to leave. She made her methodical way from flower to flower, her pollen baskets golden.

I’d like to at least learn the species I see when I sit in my red chair with my coffee. There are honey bees around too. I’ll try to figure them out as well. I remember loving book 4 of Virgil’s Georgics, devoted entirely to bees:

Of air-born honey, gift of heaven, I now

Take up the tale.

Over the years, I’ve let the oregano and lemon balm self-seed and spread. My careless style of living, as gardener at least, means that there are bees at every turn. Listen! The humming is beautiful. Drawn by scent and memory, they come to the herbs, the lemon blossoms, the flowering tomatoes, and maybe by now they recognize me too, the woman who scoops up the fallen ones, placing them carefully on geraniums, hoping they’ll recover.

And let green cassias and far-scented thymes,

And savory with its heavy-laden breath

Bloom round about…

That young queen might be the only one to overwinter after the first frost. I don’t know where the nest is but maybe that will be the logical step in this process, following the bees with their laden pollen baskets, wishing I had wings myself.

I will trace me back

To its prime source the story’s tangled thread,

And thence unravel.

redux: you can follow the phosphorescence like a pathway of stars

Note: this was posted in early August last year. Life is beginning to be busy, summer-mode, we call it, with some writing related stuff and some family visits in the coming weeks. I was reminded of last summer, the difficulties and also the pleasures.

________________

Yesterday we drove down the Coast on various errands, our last opportunity to shop in preparation for a family visit on Saturday, followed by a family wedding in Victoria next weekend, followed by a few days, all of us, on a beach near Campbell River. Oyster Bay. I’ve been thinking about it with some excitement and some anxiety. In these later years, I’m realizing that I am truly an introvert. And it seems I have a flawed history. So yes, anxiety. But also, again, excitement.

We stopped at our local Oyster Bay on the way down to Sechelt, to drop something off at a friend’s home. It’s one of the locations I think of as old coast — two shingled houses, one of them formerly a logging camp floating kitchen, and there’s a shucking shed from the business my friend’s parents ran in the last century.

We sometimes talked about having a dance in the shed, under its red roof, with the waters of the bay swirling underneath at high tide, and phosphorescence spangling the tide. Once we swam late at night in the bay and spread the phosphorescence from our hands like stars. My friend and I once canoed to the little creeks feeding into the bay, searching for the house Elizabeth Smart had lived in the second time she came to our area, not the one with the wooden board over the door, inscribed with The cut worm forgives the plough, where she wrote By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, but a later house, owned in those years by someone we know. It was demolished when it became too derelict to safely enter. Today we pulled in just behind the shucking shed and the view was what you can see in the top photograph: shallow water, moss, the most beautiful light. I didn’t want those years to end.

On our way home today, the trunk of the car filled with food — spot prawns, sausages, watermelon, cheeses, buttermilk for pancakes, wine, Persephone beer, cider from a stop at Bricker’s — I felt drowsy with nostalgia. How many times we drove this highway with our young family, on our way to the Interior, on our way to Emergency with infections of one sort or another, asthma, labour (that was me), to basketball camp or for a meal out and concerts, once a movie (Baz Luhmann’s Romeo and Juliet), swims at Snickett Park or Porpoise Bay, how many times we stopped at the bookstore or the chocolate shop, how many times. The radio kept fading in and out and anyway the music was terrible so I put on Bruce Springsteen’s Western Stars.

I lie awake in the middle of the night

Makin’ a list of things that I didn’t do right

With you at the top of a long page filled…

I do. I lie awake in the middle of the night and oh, my lists are long and regretful. What would my life had been if I knew then what I know now? I’d like to have been a better person. A better mother, a more generous friend.

We woke each morning with hearts filled

Bluebird of love on the windowsill

Now the heart’s unsteady, and the night is still…

Every morning I wake with the best person in the world in my bed and he listens to me with patience and love. What would I have done differently? Everything, and maybe nothing. The Steller’s jays are back, loud for peanuts when I come down to make coffee. You again, I say, taking them their breakfast. And you again, I say to the cat as I put food in his dish. None of them are bluebirds of love but they are reliable. My heart’s unsteady as I think of the past, what I know about it, and unsteady as I think of what’s to come. The nights are still, quiet, but in Oyster Bay, the one on this part of the coast, you can follow the phosphorescence like a pathway of stars. Where to? That’s the question.

Note: the lines are from Bruce Springsteen’s “Somewhere North of Nashville”

the gentle art

I was beginning to think I was jinxed because The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning was never available at the Sechelt Library; it was always checked out. For some months I’ve been thinking that I need to sort and winnow the overflowing rooms in this house I’ve lived in for 43 years. The books alone are, well, too many. We have a room with double-sided shelves, filled. I have a study with shelves built into one full wall and there’s no room to squeeze in another thin volume of poetry. Speaking of poetry, John has shelves upstairs with so many that he has also made piles on small tables and the floor. We never got rid of children’s books and good thing because now there are grandchildren. My mind is firmly analog, I guess, and although I use the internet (of course), I love to sit with books and look things up. There’s nothing like an atlas, for instance, or maybe 3 so you can cross-reference, sitting with them on your knee, tracing the distances from one city to another, tracing the river courses, figuring out borders. You need 3 because those borders are always shifting and it’s interesting to think about that historically, over time. And dictionaries: same.

But yesterday the library’s copy of The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning was on the shelf and I brought it home. I read most of it before sleep last night so is it any wonder I dreamed of filling boxes with…books? The author advises one room at a time. I’d like to try. I’d like to take in large bags and fill them with clothing, shoes I’ll never wear again, pots I haven’t cooked it for years, maybe even the fish-poacher Floyd St. Clair gave me when he was doing his own version of Swedish death cleaning. I remember I’d gone to have an early dinner with him and his partner David Watmough with my older son Forrest before heading down to Kits Point to see a performance at Bard on the Beach. We were using the bus and we were going to return to North Vancouver to sleep at the home of another friend after the play. So I had the fish-poacher in a large bag that I had to tuck under my seat in the tent and then carry back on the bus. That’s one item I could death clean but do I want to? Not yet. Floyd and David have been dead for years and I miss them still. (Everything in this house holds a memory.) Giving away the fish-poacher would seem so disloyal, unloving.

I could death clean the dresser holding table linens but then what happens when we need enough table cloths for all the tables put end to end for a really large gathering? (Will we have a large gathering again?) I could death clean the silver. The author recommends saving only enough plates and cutlery for the places you can set at your table. But what if? What if?

We don’t have a basement. Instead, we’ve filled our utility room with boxes of old boots, a tent, an inflatable dinghy, canning jars, two wine racks (filled, more or less, but you wouldn’t death clean wine, would you?), two vacuums, and, and, and. We’ve also filled our print shop, purpose-built to hold one printing press, then another, and cabinets of type, a table for laying out freshly printed pages, a cabinet for ink, etc. But as well as another vacuum, there’s also a wall of boxes of books, mostly copies of my own books, bought when they went out of print or else a publisher wrote to say they’re taking up too much warehouse space. Who could say no? Not me. No one wants to think of their books being shredded. But honestly, was it wise to think that somehow I could sell the books myself? I am no entrepreneur. (If you’re interested in any of them, just ask me. $5 a copy, plus postage.)

When I went to the library yesterday and found The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning on the shelf, I was thrilled. I looked at the first couple of pages and was filled with resolve. As I was leaving, I stopped at the trolley in the library lobby to see what books were being discarded, taken out of circulation. I’ve found treasures there, most recently some children’s books in French to have here for my Gatineau grandsons. Yesterday there were several copies of my book Euclid’s Orchard, the ones the library kept in their book club sets. I loved visiting a couple of book clubs who read that book, several members using library copies (while others had bought the book and asked me to sign it for them). Reader, I hesitated. I knew I had at least one box of Euclid’s Orchard in the print shop in the precarious stack against the east wall. Did I really need any more? I hesitated, as I said. But somehow The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning gave me to strength I needed to walk right past. And maybe I don’t want a copy (or two) of one of my own books with Discarded stamped on it. It’s a bit like finding one of my books listed on ABE, described as being “Unread, with fulsome personal inscription from author to fellow writer”.

One room at a time. That’s what the author advises. I don’t know where to start. But at least I haven’t added to the problem. Not since yesterday.

column

This morning it’s raining softly, after a long dry spell. A spell of heat, the grass brown, the birds insistent on their bowl being filled, a chickadee almost landing on my hand the other day in its urgency to drink and bathe.

I swam in the light rain just now. There’s a place we can leave our towels under the wide span of an ancient Douglas fir and swimming in the rain is a no-brainer: you’re going to be wet anyway…Around me, tiny pocks on the water’s surface, tiny flies, fish rising. On the other side of the lake, the pair of loons I see some mornings were calling, calling into the cool air, maybe as relieved as I was to feel the rain on my shoulders.

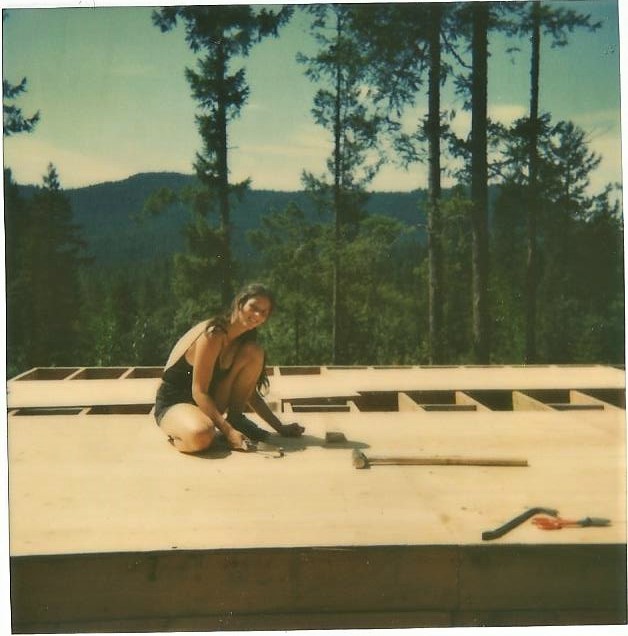

When I’d finished my swim, before getting out, I paused for a few minutes in the deep water, perpendicular, a column. How it is that I could stay in the position and not sink? Maybe I’d sink if I didn’t flutter my hands just briefly from time to time but honestly it felt like a kind of magic. I was thinking, as I hung in the water, about strength. 44 summers ago, I was nailing down the plywood that was the subfloor for our kitchen while John framed the walls. When I’d finished nailing and he’d finished framing, we’d lift the walls into place and I’d hold them upright while he’d drive the spikes through the bottom plates into the joists below. Sometimes we used a 2×4 as a brace though for the smaller sections, we didn’t bother. We had a baby who was either in the tent, asleep, or in a stroller in whatever shade we could find for him. I was 26 years old.

The reason I was thinking of that summer, the work of building a house, and how it felt to hold up a wall is because I’m figuring out some details related to my book, The Art of Looking Back: a painter, an obsession, and reclaiming the gaze*, due out next year. And to check on the details, I’ve been revisiting the manuscript. Before I knew John, before I knew the painter, before I knew much about my own strength, I spent time in Greece, mostly on Crete, but also in Athens. And I vividly remember walking up the Acropolis to visit the Erechtheion where the beautiful Karyatids hold up the south porch. I spent hours that first visit just walking around them to marvel at their bodies, their enormous dignity. I was 20. I had wide shoulders that I wished were narrow. I had a sturdy body that I wished was slim. I’d come from Crete where I wore a yellow bathing suit into the sea each morning and where I floated under a sky the models for the Karyatids would have known: blue as a book of hours.

This morning I was a column in the green water, rain falling around me, and I was remembering the shoulders of the women holding the weight of the entablature of the south porch of the Erechtheion. They are symbols of what women can do and endure. I don’t do much now but there was a time when I held up the walls of my house while a baby drowsed in the tent nearby.

I climbed the hill of the Acropolis in winter, a hill I never expected to climb, my family forgotten. I knew exactly how to find it because the hill was illuminated after dark and I could see it that first night from the rooftop of the guesthouse. The marble steps were slippery under the sandals I’d bought in an Iraklion street market. Dry stalks of summer plants fringed the path – wild oats, henbane, the desiccated leaves of coreopsis. A few seedpods from spring’s poppies. At the bottom of the hill – cypresses, pines, olives, with the prickly leaves of acanthus under their shade. Did I pay? I must have, though I don’t remember. But I do remember the Odeon of Herodes Atticus just off the path, the five gateways to the Propylaia, the temple of the Athena Nike, the Parthenon (of course) with bereted men taking photographs of tourists highlighted against it. What I remember best and most was the Erechtheion complex—the temple of Athena Polias and the Tomb of King Erechtheus, and the porch of the Karyatids or Kore. There were originally six of them, though one was removed by Lord Elgin in the first decade of the 19th century and sold to the British Museum; a replica of the lost sister stood in her place when I was there. In 1978, the remaining five maidens were removed to the nearby Acropolis Museum and replicas installed in their place. But in 1976, they stood in their original beauty, holding up the entablature of the porch on the south side of the temple; and for me they became profound emblems of strength. Their bodies were foundational, structural; they were not the objects of anyone’s gaze, or if they were or had been, it was immaterial after 2500 years. Their own eyes were farseeing. Their clothing closely fit their strong bodies, one leg taking the burden of the building’s weight, that leg bent forward to demonstrate their strength. From behind, I could see the intricate braiding of their long hair, thick and bold, serving to enforce the strength of their necks as they support the burden of the entablature.

*I have written about this book in the past, using its earlier working title: Let A Body Venture At Last Out of its Shelter. But it will be published by Thornapple Books as The Art of Looking Back: a painter, an obsession, and reclaiming the gaze.

creatures

A fuzzy bee (in both senses) in the vetch that grew with the Cupani and Painted Lady sweet pea seeds and which I’ve let go because honestly who can say which is lovelier? Purple bells of vetch, bi-coloured pea blossom. This bee moving from flower to flower, a yellow-faced fellow-traveller in the oregano.

Chestnut-backed chickadees making a fuss at the birdbath to let me know it was empty. They waited in the mountain ash only as long as took to fill the shallow bowl, descending in a busy flutter.

Last night, at my desk, I looked out to see a coyote at the edge of the grass, sniffing, sniffing, turning once, and when I went upstairs to look out the high window, I watched it emerge from the lane where we turn our car, watched it look, first towards the house, wondering maybe about the cat, then down the driveway where the grouse leads her young in the brush at the bottom, and off it trotted away.

Driving back from supper at the Egmont pub last week, not yet at the main road, taking our time in the falling light, we saw a bull elk not five feet from the car, standing where the road fell away into a yard, his massive antlers level with our window, close enough to see the golden velvet. Close enough to smell the body through the open windows.

Swimming this morning, the swallows swooping over me, foraging for their breakfasts, I saw a dragonfly hovering over the shallows, its wings checkered in the early light.

“The man on the other end of the phone was quiet for a moment.” (Remembering Andrew Scott)

This morning I am remembering Andrew Scott, writer, editor, historian, adventurer, husband, friend. He died earlier this week, too young, and yesterday, at lunch with friends, we were talking about him and I realized I’d put him in my novel Easthope, unnamed, but very much himself: curious, helpful, interested, knowledgeable.

A man Marty and Sam knew down the Coast called her one day to say he understood she wanted to know more about Doriston. Yes, I do, she replied, what’ve you got? I’ve only been there once, he told her, on the winter bird count, but I wrote about it for one of the Vancouver newspapers and I can send you my piece. It’s kind of haunted. Sam says you were there once too? I’ve had it in mind to call you before but I’m just back from the bird count again, though not the Inlet part of it, and I was reminded.

She told him about their trip there, how she was looking in a way for traces of the Anderson girls, though she knew they’d lived a little ways away from Doriston proper. But I wanted to see what they’d have seen in their daily lives, she confessed. The weather, the vista across water. I dreamed about them before I even knew about them…and she stopped, realizing it was a pretty odd thing to tell a stranger. But he listened, and said, There are places on this coast that have that effect on me. The sense of the past superimposed on the present, or maybe it’s vice-versa, but I want to know more, to know it in every sense.

Yes, that’s it, sort of. And with the girls, I wanted to pay them the respect of remembering them, I think. I’m a painter, maybe Sam and Marty told you that, and so I’ve tried to paint the moment their boat went down, I’ve tried to imagine what happened after. Not in a macabre way, though I guess it might sound so as I describe it, but to make a connection with them and their experience. I was a teacher for years, mostly art, and mostly older kids. So when I read the Doriston notebook in the Museum, I was more than impressed that children, really, could do that fine work of researching their community, describing its weather, its history, its social structure. One of the 3 sisters, the older one Mary, is named in the notebook as one of the contributors, so I felt I got to know a little about how she saw the world. A world she knew intensely and well, and then she was gone. I wonder what it must have been like for their parents.

The man on the other end of the phone was quiet for a moment. They moved away. You probably knew that. And there were no longer enough kids to keep the school open. So in a way it was the end of that chapter of Doriston’s history. Though others stayed, and a few live there to this day. I don’t think I’d want to live there myself, it’s too remote, too far from services we think we need, or I do anyway, but I want to know it continues still.