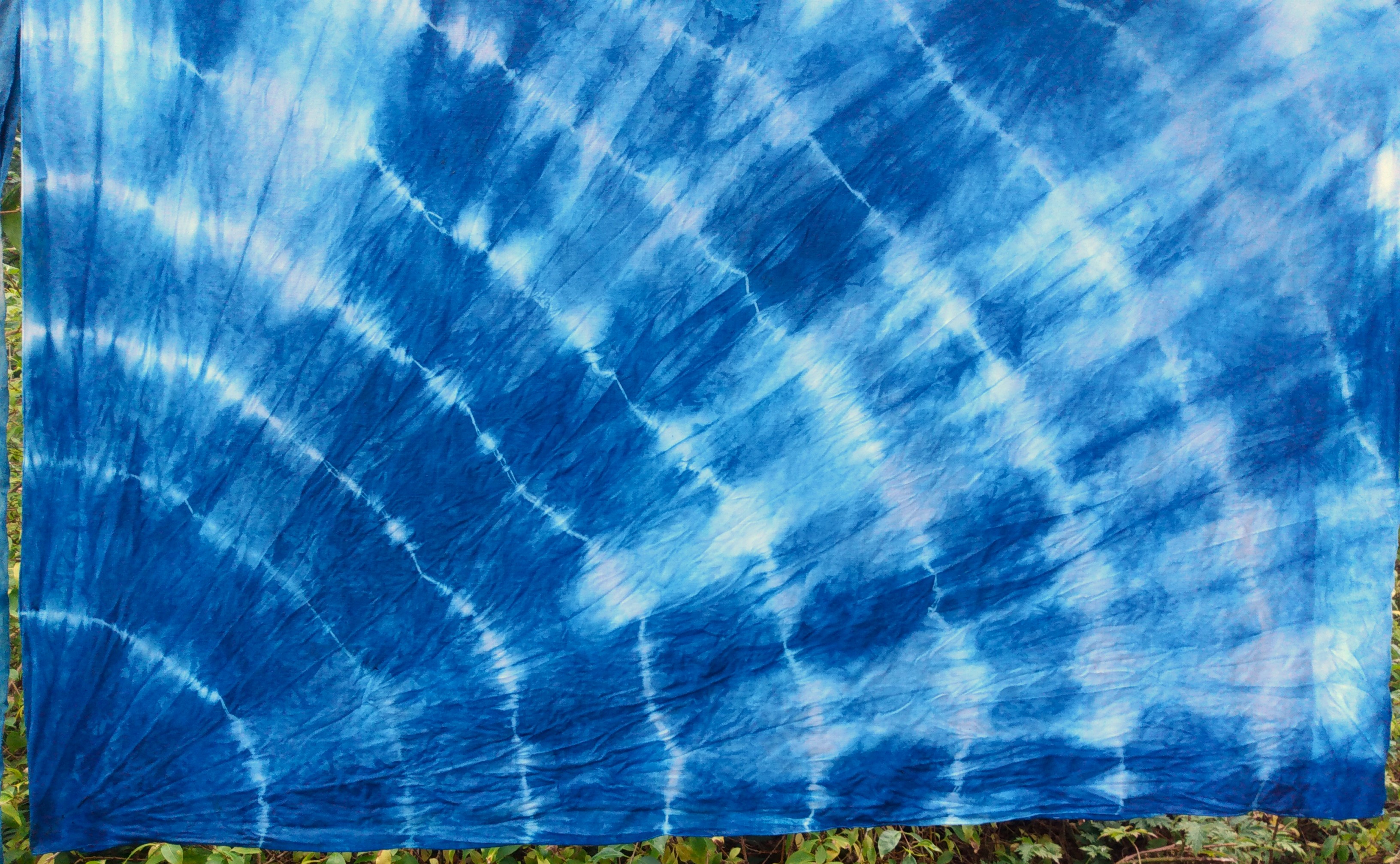

Yesterday we were headed down to the lake for my swim, maybe one of the last lake swims of the year because the air temperature was 8 degrees celsius and the water wasn’t much warmer, and we were talking about the big dye lot I’d done the day before. Actually, as we were on our way to the lake, one last length of fabric was waiting to be dyed–coarse linen I’d batiked salmon onto and then immersed in indigo a few years ago. It was the last of the dye and it didn’t really take. So I thought I’d overdye the linen and see if I could enhance the colour a bit. So we were talking about how the whole experience surprises me over and over again. I know one can approach indigo (and other natural dyes) in a systematic and scientific way, taking ph readings and so on, but my method (if you can call it that) is to give myself up to the process. I tie, sometimes I clamp with little squares of plywood and dollar store clamps (or clothes pegs), sometimes I use wax to make images for surface design. I wrap fabric around pvc pipe or wooden poles. I gather fabric around beach stones and tie them into place, sometimes randomly, sometimes in a grid, and then I prepare a vat of dye. The vat is a big plastic tub that’s otherwise used for garden work and I set it up on a long cedar bench by the vegetable garden. That way I can immerse the fabric into the vat and wait for 20 minutes or so, removing it to rest and oxidize on the bench before repeating the whole thing 6 or 7 times. While the fabric is immersed or while it’s resting, I can check out the cabbages (huge savoys I started from seed bought in the Mercado do Bolhão in Porto in March) or just look at the roses growing over the garden gate.

I never know what to expect. Or perhaps I mean that I don’t expect anything. I don’t know enough about this pursuit to have expectations. I don’t have confidence in my own grasp of technique. And I am always thrilled with what happens–the surprises of pattern, the intensity or not of blue, how string can mimic ripple or eelgrass, how the wrapped stones become snow angels or owl wings or jellyfish. If I knew enough to manipulate more decisively, would I be happier? I don’t think so.

As we went down to the lake, I wondered how the things I’d been preoccupied with all spring and summer found their way into the fabric. Those jellyfish drawn to the light of our boat anchored in Hemming Bay on East Thurlow Island, the ripples generated as a trout surfaced for insects while I swam on a September morning in Ruby Lake, the turbulence of my heart and mind echoing the waterways of the planet, and the memory of a walk on the Brem River estuary in April, watching for grizzly tracks. It’s like writing, said John. We think we are writing about one thing and we discover something else entirely. But the difference, I said, is that when I’m writing, I don’t have expectations necessarily but I do have some confidence in my ability, my knowledge of technique. I know the hoard of imagery and experience I’m trying to access. This is so different somehow. I’m reminded of Ann Hamilton’s wonderful essay, “Making Not Knowing”:

One doesn’t arrive — in words or in art — by necessarily knowing where one is going. In every work of art something appears that does not previously exist, and so, by default, you work from what you know to what you don’t know. You may set out for New York but you may find yourself as I did in Ohio. You may set out to make a sculpture and find that time is your material. You may pick up a paint brush and find that your making is not on canvas or wood but in relations between people. You may set out to walk across the room but getting to what is on the other side might take ten years. You have to be open to all possibilities and to all routes — circuitous or otherwise.

I was dyeing linen and cotton with indigo dye. I was thinking about the life I am living with its beauty, its damage (to myself and others), the lost opportunities, the blessings, the disappointments. In the woods behind the garden shed, a pileated woodpecker was pecking so loudly I thought John must be hammering boards together. In my heart, both joy and bitterness. The disposable gloves kept slipping so that I have rings of blue around my wrists. There are so many things I want to say. This morning, a basket of blue fabric, washed with mild detergent, ready for the winter. I have gathered my sharp needles, my strong thread, the tiny golden scissors shaped like a crane.