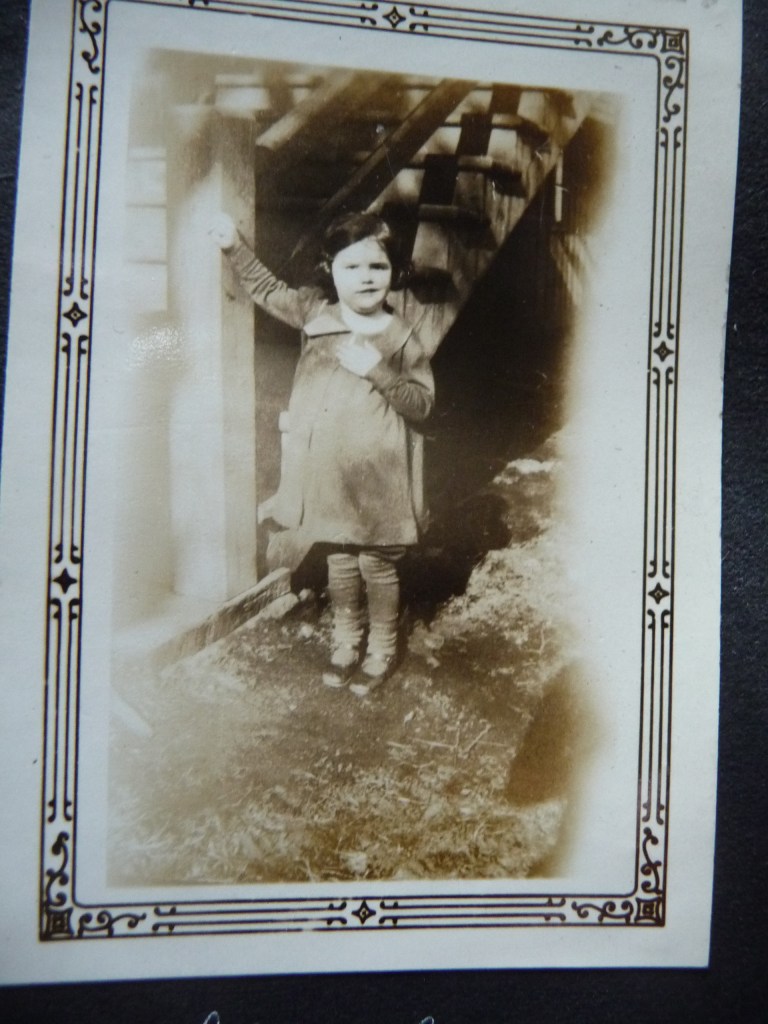

We spent three nights in a little house on the banks of the Thompson River in Kamloops. It was a gathering: two of my three brothers, their wives, and us. (We missed the brother who couldn’t join us.) And on Sunday, on Mothers Day, it was good to sit with my sisters-in-law and talk. Two of us have gone through difficulties with our children, learning late of some issues and animosities. We talked about that and the sister in our group who hasn’t experienced that said, I just don’t want to ask them about any of this. With my brothers, we talked about our parents (among everything else). Our father was difficult in many ways but also memorable. So many times over the three days I heard his expressions, the ones my children use, and maybe now their children as well. Our mother: well, she holds a different place in our memories and in our hearts. That’s her in the photograph, on a stoop in Belmont Park near Victoria, where we lived on two different occasions, in the married quarters provided to families of those serving in the armed forces. Our father was in the navy, a radar technician, and he was often away for months at a time. Our mum did her best to keep the household running smoothly. The laundry was done every Monday morning–she had a wringer washing machine–and she made our bread, kept us fed, walked us to places where we could swim (she didn’t drive), made sure birthdays and Christmases were memorable, though there wasn’t much money.

On Sunday, at my request, we all drove down to Nicola Lake along Highway 5A, taking a picnic. My older brother stopped at the places I asked him to stop along the way and my brothers and husband brought down chairs to the lakeshore. We sat in the sun. I swam. An osprey fished just beyond the beach. John and I shared stories of our many camping trips to Nicola Lake. Our children loved it. They’ve taken their children. I remember how we’d wake to the sound of the Clark’s nutcrackers in the Ponderosas and how everything would be covered in fine pollen. When the mornings heated up, the scent of sage was beautiful. I remember how our children rolled down the soft grass into the kikuli pits by the beach. How they loved the evening talks by the naturalist in the small amphitheatre. Once, the naturalist handed around a jar with a black widow in it! We’d walk up the hill behind the campsite to the remains of a volcano and bring a few stones back, riddled with tiny holes.

That night I was awake for an hour or two, thinking about families. About mothers. Was I grateful enough for mine? I wasn’t then but I am now. She did her best. Her own origin story is sad. She was given away at birth because her mother, a young-ish widow with 5 young children, became pregnant and the father wasn’t about to marry her. There’s a story there that I’ve only come to know, all because of sending off a DNA sample and being patient enough until the matches that arrived in my email box began to make sense. When I say she was given away at birth, that’s exactly right. A woman took her, accepted money for her care for the first while, and in the 1931 census, my mother is described as a “boarder” in the home. She was 5 years old.

The Thompson River flowed by the little house we stayed in for 3 nights. We sat outside with wine and beer and talked about everything under the sun. On Sunday every mother in our company received messages or phone calls from their children. We shared them. We laughed, told stories, remembered our own childhoods, in sunlight, and when the clouds moved in. I told my brothers I’d put my share of our parents’ ashes under a tree I see every day. I planted daffodils there, wildflowers. We all put a small portion of them into the sea near Tofino not long after they died. One brother still has a bag of them in his house. They are long dead now, but everywhere, my mother most of all.